A Perfect Circle: Eat The Elephant album interview

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Released in 2018, A Perfect Circle’s Eat The Elephant saw Tool singer Maynard James Keenan and reuniting with guitarist Billy Howerdel for their first album in 14 years. Classic Rock sat down with the pair in London to hear tales of death stares, Axl Rose and the end of the world.

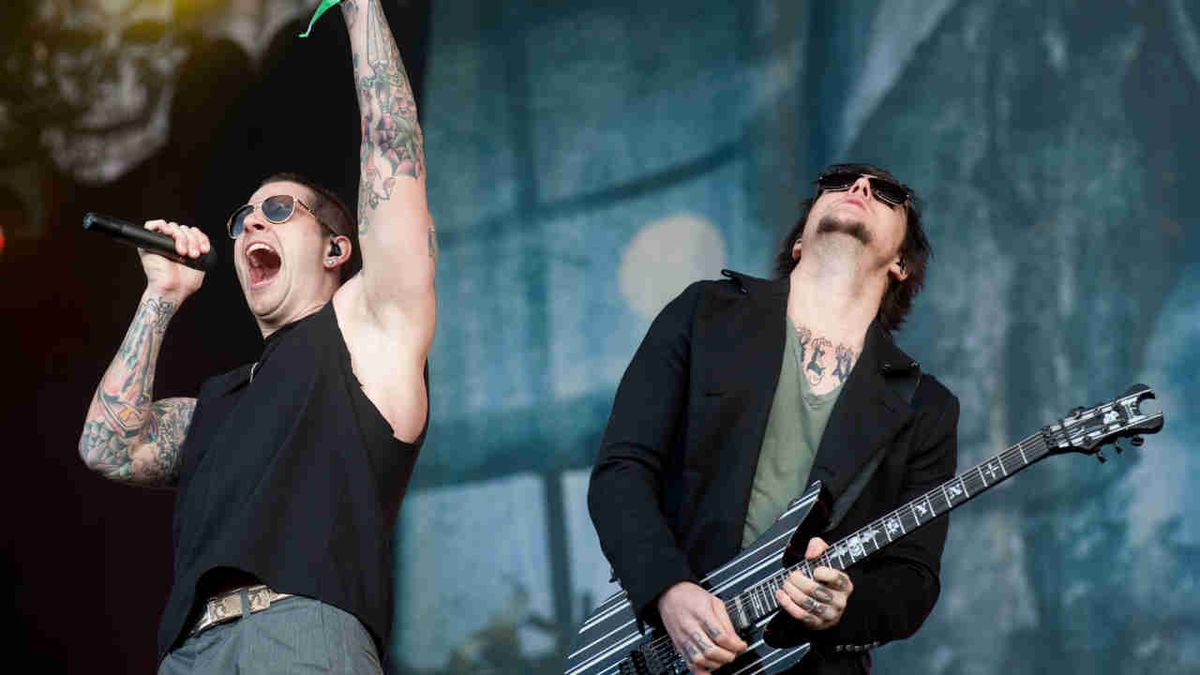

Billy Howerdel vividly remembers the first time he saw Maynard James Keenan on stage. It was 1991, and Keenan’s band, Tool, were playing hip Hollywood venue Club Lingerie. Howerdel knew of the band via mutual friends, and he’d headed over to check them out.

The demo tape Howerdel had heard sounded full-on, but he wasn’t prepared for the intensity in the room that night. As the band stretched and pummeled the wet clay of their music, a mohawked Keenan fixed Howerdel with a death-ray stare; he didn’t blink, just kept looking at him unnervingly. Howerdel worked as a guitar tech for LA funk-rock heroes Fishbone, and he was used to maverick musicians, but this was something else.

“He had this fifty-yard stare, and I was in the target zone,” says Howerdel. “I thought the guy was ready to jump off stage and have a ruckus.”

Disconcerted, Howerdel moved out of Keenan’s eyeline. The guy on stage didn’t notice. He just carried on staring ahead, unaware and unflinching. “That’s when I realised it wasn’t me,” says Howerdel. “That’s just how he was.”

What Howerdel didn’t have know that night was that he would not only enter Keenan’s close orbit, but also eventually form a band with him.

Across the three albums they released in the early 00s, that band, A Perfect Circle, forged their own path. Their muscular but intelligent songs weren’t uncommercial, but nor were they pandering to anyone else but themselves. Like Keenan up on that stage, their approach was simple and uncompromising: this is how it is, take it or leave it.

There has been a long gap since then. A Perfect Circle haven’t been entirely absent – like some mid-sized comet, they’ve reappeared every few years, for short bursts of touring activity, most recently in 2017 – but there’s been a definite lack of activity on the studio front. A large part of this is down to Keenan’s other commitments, among them Tool, his other band Puscifer, and the vineyard he owns and runs in Arizona.

That situation has changed recently. Howerdel and Keenan have finally found time to make their first new record since 2004’s George W Bush-era covers-come-protest album eMOTIVE. Titled Eat The Elephant, it busts the boundaries of what they do wide open. Its sound ranges from the hypnotic, piano-led title track to the perversely poppy So Long, And Thanks For All The Fish. “It’s less focused,” Howerdel says. “By that I mean there are more colours.”

The lengthy gap between records has served as a large evolutionary jump. But it doesn’t explain why they’ve decided to come back now.

“It just felt like it was time,” says Keenan, thankfully without the basilisk gaze that transfixed Howerdel all those years ago. The two men are sitting in separate, equally characterless business suites one floor apart, in a discreetly expensive hotel that overlooks London’s Piccadilly Circus.

“A lot of different factors came together,” he continues. “I saw a window to get it done, and Billy seemed ready. And it seemed like a perfect follow up to eMOTIVE.” The man who recently described Donald Trump as “a disgusting turd” gives an ironic half-smile. “We thought things were bad then.”

Maynard James Keenan describes Billy Howerdel as “stubborn”, a trait you suspect is no less applicable to Keenan himself. “He’s definitely one of those guys who writes in his closet and is constantly tweaking things, and will never actually release it,” says the singer. “Maybe what I bring to the table for him is a sense of urgency: ‘We have exactly ten minutes to do this, so get over whatever it is you’re apprehensive about, and shit or get off the pot, cos I gotta go.’”

You can see he means. Where Keenan is polite but businesslike, with a parade-ground directness (no surprise, given that he joined the US Army for a couple of years), Howerdel has the thoughtful caution of a man who didn’t get into the music business to do interviews. “I didn’t have the burning desire, ‘Look at me, look at me,’” he says. “I enjoy the making of things, getting into the details.”

A look at his CV backs this up. For much of the 1990s, Howerdel was a behind-the-scenes guy, working as a guitar tech for the likes of Fishbone, Tool, Nine Inch Nails and David Bowie. He studied the work ethic of the bands and musicians whose orbit he was in (he cites NIN’s Trent Reznor as a particular inspiration), and watched as technology changed, opening up a range of possibilities. All the while, he was working on songs that would form the basis of A Perfect Circle.

“I was always writing music in isolation,” he says. “When I was on tour, I brought a big suitcase with guitar and bass. I was the pain in the ass in the road crew, crowding out the bus bay.”

He’d half-heartedly tried to get a band off the ground earlier in the decade, but it would be Keenan who eventually strong-armed him into it. When Howerdel needed a place to stay after coming off a David Bowie tour in 1996, Keenan offered him his spare room. Howerdel played Keenan the music he was making, and the singer liked it. If he was going to do something with it, Keenan suggested, then he’d love to sing on it. It seemed like a perfect plan. And then Axl Rose got in the way.

![A Perfect Circle - The Doomed [Official Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/SDvfbvuJtS8/maxresdefault.jpg)

Not long after he moved in with Keenan, Howerdel got a call asking if he wanted to work on a new Guns N’ Roses album. Axl had recruited former NIN guitarist Robin Finck, who called to ask if he’d be up for “programming strange guitar sounds”.

Howerdel’s time in the Guns N’ Roses inner circle lasted two and a half years. Often it would be just him and Axl sitting together in a room together for hours, working on one piece of music while the band recorded in another part of the studio. Today Howerdel speaks respectfully of Rose.

“He and I hit it off. He had this desire to make the greatest record ever, which is a tough thing for anyone to set out to do. But there were so many moving parts. There was a lot of money, there was a lot of time, there were a lot of people. It didn’t convince me that was the way to go.”

The irony is that it’s taken Howerdel and Keenan 14 years to make the new APC album – exactly the same amount of time it took Rose to create Chinese Democracy. The guitarist says that he had enough songs five years ago to at least start the ball rolling on a new album. Was the delay frustrating?

“No, because there was no way of hurrying it up,” he says. “The music is being written constantly. If I have a bank account of enough songs, I feel the confidence of being able to answer the call if Maynard says: ‘Hey, I’ve got a window of time. Do you want to get together?’”

Did you ever consider making an A Perfect Circle album without him?

“No,” he says, looking perplexed that anyone would think he’d even consider it. “He and I are the foundation of the band. That’s where we started. We set out to do it together.”

Maynard James Keenan doesn’t recall the Club Lingerie gig where he made such an impression on Billy Howerdel. His first solid recollection of his future bandmate dates back to when Tool supported Fishbone, the band Howerdel was tech-ing for on tour in France sometime in 1991. “Sweaty cheese, stale bread, playing to 12 people, going, ‘What the fuck are we doing here?’” he says drily. “All of a sudden you wake up one day and you know everybody.”

Both men have come a long way since then, though Keenan’s journey has been more public. He’s still best known as the singer with Tool, a band who have spent three decades twisting rock into startling new shapes (any talk of that band’s long-gestating new record is strictly off-limits today, enforced by the amusingly passive-aggressive presence of a management representative tapping away at a laptop in the room). Keenan also leads Puscifer, a deliberately uncategorisable collective that allows him to indulge in his stranger, funnier side.

And then there’s the vineyard and wine cellar he set up in Arizona over a decade ago. Wine making is Keenan’s great passion. Where he can be cagey about music, he’s open and enthusiastic about wine, from his first introduction to that world (“There was a very specific bottle of wine, with a specific meal, in a specific town, that changed the way I thought”) to the philosophy behind it all (“The idea of expressing a place, and having that story evolve in a bottle over time”). He currently employs 40 people. He’s as serious about it as he is about any of his bands.

Despite his numerous other ventures, A Perfect Circle is no afterthought for Keenan. The delay between albums is down to his rigorous approach to his craft. He refused to commit if he couldn’t give it his full attention. “It just happened that there was a lot occupying my attention,” he says.

It’s impossible to properly gauge the working relationship between Keenan and Howerdel just by sitting with them, separately, for a couple of hours in a hotel room, but you could take an educated guess and say that neither would put up with the other if they were a dick. What does Maynard get out of working with Billy? He smirks.

“A headache. I’m kidding. He gets a bigger headache than I do, for sure. Working with Billy definitely helps me understand how I work well, how I don’t work well.”

Did he tell you what kind of album he wanted to make? “If he did, I didn’t hear it.”

Did you tell him what kind of album you wanted to make? “I made the kind of album I wanted to make. He’s very focused on music, how that’s all going to come together. When it comes approaching concept, I tend to be the bull in china shop.”

There’s a very clear sense that Keenan doesn’t like to take things apart and lay them on the ground so other people can see how they work. That applies equally to inter-personal relationships, to the creative process and to his lyrics. The album’s title, Eat The Elephant, is a vivid phrase that broadly means tackling a big task one small step at a time. It could apply to the process of making the album itself, but it could just as easily mean something altogether more oblique. The faint whiff of social or political commentary hangs over new songs such as The Contrarian and Delicious, but nothing’s ever explicitly spelled out, on record or in person. ‘Work it out yourself,’ is the unspoken message. ‘Or don’t. Whatever.’

![A Perfect Circle - Disillusioned [Official Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/BIsH686xWl0/maxresdefault.jpg)

There is one track on Eat The Elephant that does crack open the door into Keenan’s mind very slightly: the melodic yet scabrous So Long, And Thanks For All The Fish borrows both its title and its comic imagery of dolphins vacating Earth from the Douglas Adams novel of the same name, the fourth book in the Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy ‘trilogy’. Keenan is a fan of Adams. Both share a fairly dim view of humanity.

“I love the images in his books of people laying on the ground with bags on their heads because they might survive the destruction of the planet,” he says, laughing. “I wrote this song and I couldn’t figure out how to title it, because it was so sarcastic, so upbeat and destructive. And then I went: ‘Fuck, it’s Hitchhiker’s.’ The dolphins leaving the planet: ‘Bye! Good luck!’”

Keenan is an avid fan of comedy. He was friends with visionary stand-up provocateur Bill Hicks, and he references stoner comics Cheech & Chong and twisted British sitcom The League Of Gentlemen alongside Adams today. And anyone who appears on stage wearing a riot cop’s uniform or a Madonna-style bustier and ponytail, as he has, really isn’t taking things too seriously. The only snag is that not every gets his sense of humour.

“A lot of people get really literal, especially when you read jokes in print. That’s the beauty of podcasts – you get a sense of timing and cadence. With print – emails, tweets – sometimes you miss the joke, because you can’t capture sarcasm.”

Keenan says he has conflicting feelings about the internet. He likes what it offers – “an entire collective unconsciousness at your fingertips” – but doesn’t like what it’s turned people into. This is the only time today he sounds exasperated.

“The biggest challenge is the sense of entitlement,” he says. “It’s built a generation of people that have expectations that aren’t sustainable. Having everything handed to you. Free music, free movies. There’s a generation who don’t understand what it took to make the thing. There will be some kind of wake-up call when things are no longer free. There’ll be a lot of crying.”

In a weird way, A Perfect Circle are the most confrontational band currently operating, although they’d probably recoil at the tag. While others take up cudgels and megaphones on the steps of Wall Street, they’ve let their mere existence do the talking. Their message is simple: you’re either with us or we’re not interested.

The stand they’ve taken against people filming their gigs is a case in point. They declared that anyone caught recording at shows on their 2017 tour would be ejected. It was a bold move, and one that anyone who has been forced to watch a gig through other people’s phones wishes would have been made sooner by someone else. Still, it caused a predictable storm amid those it was aimed at.

“Why is it any different to going to a movie or a play?” says Howerdel. “Get your camera out there and see what happens. And what are you going to do with it anyway? Watch it ten times over?”

“We got yelled at quite hard,” Keenan says. “People have this black mirror that they’re waving around as if that’s part of the experience, and I disagree. We’re presenting something for you, there’s a guided tour here, pay attention. You’re coming into this thing hopefully with a sense of reverence for the work that went into it. So if we have to force that courtesy, I will. I’m not trying to be a Nazi prick, I’m trying to show you something. You paid for me to show you something, I didn’t pay for you to show me something.”

He wears the expression of a man who couldn’t care less about what anyone else thinks. Even if you disagree, there’s not much you can do about it. That’s how it is with A Perfect Circle. Take it or leave it.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 248

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Source link