Jon Bon Jovi: The Classic Rock Interview

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

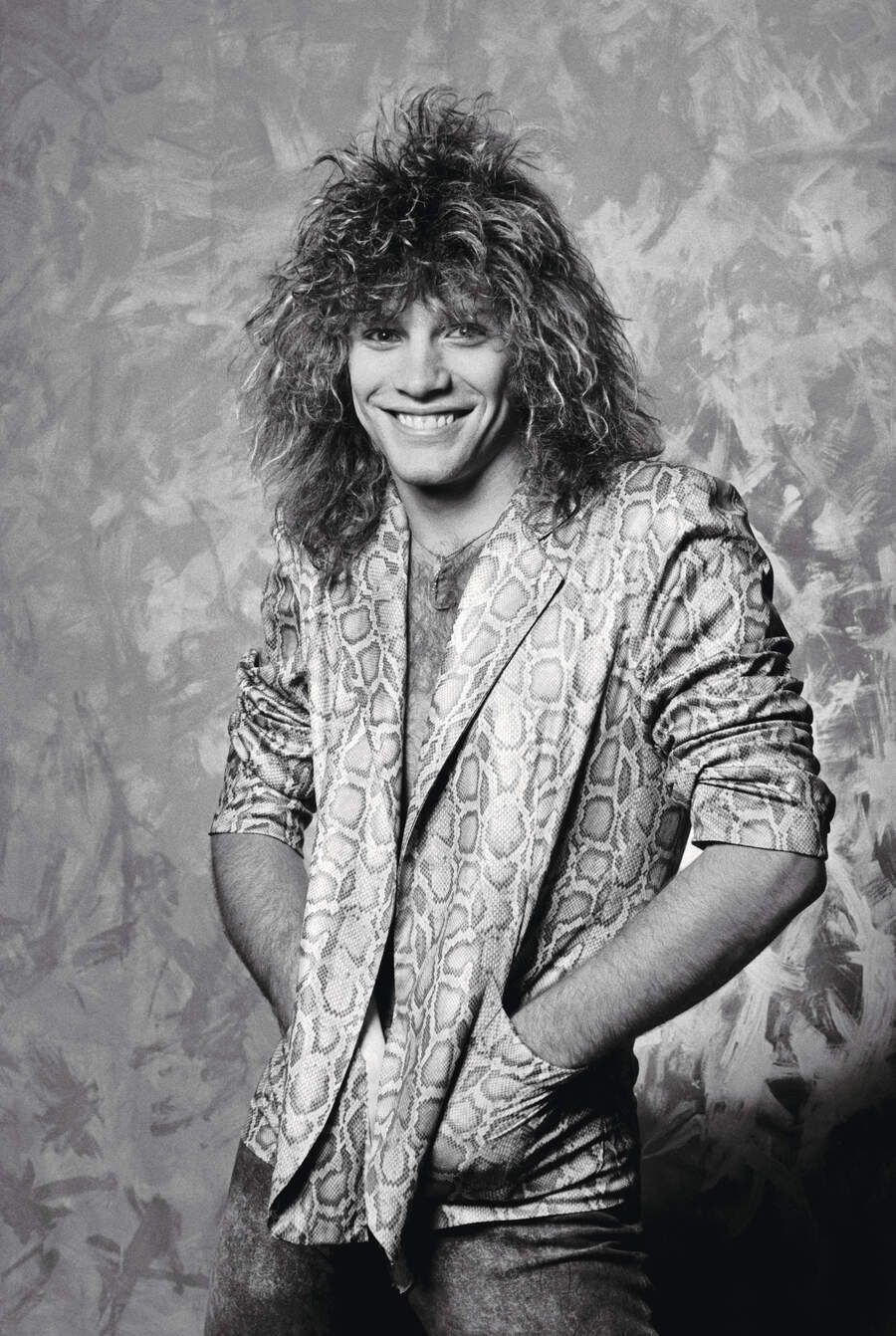

November 7, 1979. The Atlantic City Expressway are on stage at the Stone Pony club in Asbury Park, New Jersey, performing a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s The Promised Land, when an audience member jumps on stage, grabs the mic and begins singing the second verse. It takes Atlantic City Expressway’s vocalist John Bongiovi a beat to recognise the interloper as the man who wrote the song.

“I’m a seventeen-year-old kid and suddenly I’m sharing a microphone on stage with the biggest rock star in New Jersey,” he – now Jon Bon Jovi – marvels, 45 years on, looking back on that night while seated on a sofa in an upmarket London hotel room. “I’ve got high school in the morning, and the teacher just sounds like ‘Wah wah wah, wah wah wah’, because I’m thinking Bruce will probably want me to come over to his house tomorrow, now that we’re friends. I had rainbows and unicorns in my head, like an acid trip, because now I had seen the world in colour.”

An astute, driven polymath, a music industry lifer with 130 million album sales to his name, it’s a long time since Jon Bon Jovi had his head in the clouds. The singer/guitarist/band leader is in London to talk up two new projects: his band Bon Jovi’s sixteenth album, Forever, released last month, and Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story, an insightful four-part Hulu documentary, directed by Gotham Chopra, who has previously made films about American sporting icons Serena Williams, Kobe Bryant, Tom Brady and others, which aims to shine a light on “a 40-year odyssey of rock’n’roll idolatry”.

It’s a measure of how hard Bon Jovi has been working during his four-day stay in London that this afternoon, mid-sentence, he’ll cast a glance across the River Thames, spot an iconic landmark on the South Bank, and exclaim excitedly: “Wait, is that the London Eye?” as if he’s only just now had a moment to take in his surroundings. But then as Thank You, Goodnight makes abundantly clear, JBJ has always had his eyes fixed on the prize. “There was no Plan B in my life, ever,” he states emphatically at one point. “It was all or nothing.”

With that said, the 62-year-old hasn’t forgotten what it’s like to be a rock’n’roll dreamer, hoping for a break. At the end of our hour together, I ask him if he’ll record a video message for a friend, an aspiring singer-songwriter who’s ploughed thousands of pounds of his own money into recording two albums, encouraging him to keep the faith.

Graciously, after quickly checking that his hair is looking good – it is – he does as requested, ending a genuinely touching inspirational speech with the words: “As you know, writing a song is the most euphoria one can ever feel, so keep writing ’em, bud, one of them is gonna click. And as long as they move you, fuck everybody else, right?”

As he passes my phone back, I ask him what advice he’d give to his teenage self, that New Jersey kid dreaming of following in his hero Bruce Springsteen’s footsteps, and his reply comes instantly: “I’d say: ‘Take the time to enjoy it a little more.’”

Do you remember who John Bongiovi was before music entered your life?

The earliest recollections I have of the twelve-year-old me are very similar to the me I grew up to be, with maybe more of an athletic focus, because I liked to play baseball and football. I had a very typical middle-class upbringing in New Jersey, and initially it was uneventful.

Your mum was a florist and your dad was a barber, and they’d both served in the Marines.

They did. That’s how they met. So was yours quite a disciplined household? I didn’t think so. And probably nowhere near the upbringing that they had as children. It was a different generation by then. I was born into the era where John Kennedy was the President of the United States, and so The Dream in America was alive and well.

What was the first music that felt authentically yours?

I remember buying the first Aerosmith record, and by the mid-seventies it was Thin Lizzy, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Queen, Zeppelin, Alice Cooper, Elton… mainstream, heavily English-influenced rock’n’roll.

Did punk rock impinge on your life?

For the big brothers of my buddies, yes. We were very aware of The Dictators, The Dead Boys, Ramones, the Pistols, obviously, but it wasn’t my personal calling. I didn’t dislike it, but it was music for our big brothers.

Do you remember your first time on stage?

It was a talent show in Sayreville, New Jersey. I sang Strutter by Kiss, Johnny B. Goode, and Taking Care Of Business by Bachman Turner Overdrive. I did not win.

But you gave it a shot.

I gave it a shot.

The standard potted history of Jon Bon Jovi is: kid wants to be a rock star, kid works in his cousin’s recording studio, kid gets a break with the song Runaway, kid becomes a rock star. But watching the Thank You, Goodnight documentary, it’s obvious that you put in the hard yards, first with Raze, then the Atlantic City Expressway, a covers band that I guess was doing good business, and then The Rest who did original songs.

Atlantic City Expressway weren’t doing great business, really, but we were performing. I was still in high school, and we were playing in nightclubs where the other bands were ten years older than us, so being that young we stood out. But I knew that to get off that circuit I needed to write my own music.

What did The Rest sound like?

Power-pop/new wave, like New Romantic music, Elvis Costello, whatever. Not great.

You started to properly take control of your own destiny with Jon Bongiovi & The Wild Ones, a band who were heavily influenced by the Jersey Shore scene.

Yeah, and that scene was inspiring. Because remember there were ten Asbury Jukes and seven members of the E Street Band, so that’s seventeen iterations of Santa Claus who would be in one of the local bars on any given night. You could literally tap them on the shoulder, buy them a beer and ask them anything. And those guys were so kind and generous with their time. Like, Southside Johnny produced the second set of demos that The Rest ever did, and Roy Bittan, from the E Street Band, first played that keyboard riff you know today in Runaway.

And then you went to work at The Power Station studio in New York with your cousin Tony.

He’s a distant cousin, I’d never met him, but my dad asked him to come and see me perform with The Rest, and he told him: “The band’s not very good, but your kid’s got something going.” So after high school, in September 1980, I called him up, and he allowed me to run errands at the studio.

In the documentary, you say that sometimes you had to bring drugs to the studio, and sometimes you had to bring girls. Could you elaborate on that?

No, I’m gonna leave that there. But that was the era.

You were there when Queen and David Bowie recorded Under Pressure. That must have been kinda mind-blowing.

That’s my recollection. I’ve asked my cousin Barry to verify this, saying: “Am I crazy, or is that true?” And he said: “You’re right.” I’m putting this in a big parenthesis for fear that my memory has slipped, but I do believe that I watched in Studio A as the two of those guys sang.

Runaway was a radio hit before Bon Jovi, the band, existed. But initially, when you sent it to record labels, no one was interested.

I didn’t get any answers from anyone, no. But, in retrospect, did it ever actually land on anyone’s desk? Did it ever make it out of the mail room? I’ll never know. I’d sent it out to all the labels with a handwritten note, because that was the only way I knew to approach them. It wasn’t like anyone I knew in Jersey knew the president of a record label.

How did it feel to hear your song, your voice, on the radio for the first time?

I was overjoyed. I remember hearing it on the radio in the car, and it made me want to roll the windows down and drive faster. I wanted the police to pull me over so that that I could say: “That’s me on the radio!”

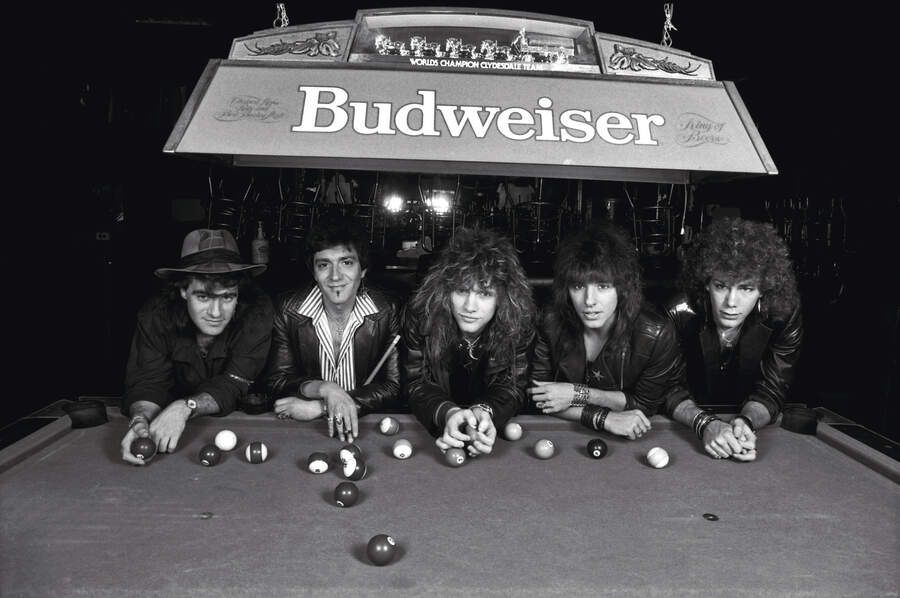

So now you just needed a new band.

Yes. At the time, I was playing a club called the Fast Lane at least two nights a week, and I was capable of drawing – if I’m generous to myself here – maybe a hundred and twenty-five people to come and see me play with various iterations of the Wild Ones. So I get this song on the radio, and the quality of my band members I thought could be better, so I started seeking out guys that I’d seen around.

I thought that when I got this new iteration together – which did not include Richie [Sambora] – that it would last for three weeks, because I figured that after three weeks this song will have run its course, but maybe a hundred and fifty people would come to see me now, and I could build from there. That was the mind-set.

With Richie, what was it that you recognised in him that made you think: “This is the guy”?

He came to see us play when Snake Sabo [Skid Row] was filling in on guitar. Dave [Bryan] was playing keyboards because he had been in the Expressway, Alec [John Such, bass] I’d recruited from a cover band, and Tico [Torres] was the best drummer I’ve ever fucking seen. Alec got Richie over to see us. So when Richie shows up, he comes in the dressing room, and we make small talk and I like his presence.

So I say: “Well, what are you into?” And he says: “I like Bad Company, and Zeppelin, and I’ve got my own band, and we’re putting out an EP.” So we got together once, we started to dabble in writing, and it worked. Then Runaway exploded, I got a record deal, and Richie said: “Okay, I’d rather come with you, with a record deal, than keep slogging it out with my band.” I liked him, he was a talented guy, and he could sing. So that was it – Bon Jovi.

What do you remember about the first time you played in England?

It was the Kiss tour, in 1984. I remember we started in Brighton, and Kiss were out with their spray cans of paint, fixing up their set in the afternoon, so that blew away your childhood memories of watching them at the [Madison Square] Garden! One of our roadies had worked with Phil Lynott in Grand Slam, and I was so excited about that. So fuck yeah, I remember being here. I remember Malcolm Dome giving us a good review in Kerrang! We thought we’d made it.

The old cliché is that you’ve got your whole life to make your first album, and then, like, get six weeks to make your second one. Did your second, 7800° Fahrenheit, feel rushed?

It didn’t set the world on fire. It didn’t, but we did the best we could with our limited knowledge of any aspect of record making, and no great guidance from either the record company or management. Let’s not be too harsh, it did okay – 750,000 record sales in America – so the curve was still going upwards.

Did you have to set your ego aside when you brought in songwriter Desmond Child for the next album, Slippery When Wet?

[Sighs deeply] Okay, let me clarify this again, which I’ve probably done about one hundred times already. I saw from afar Bryan Adams, who I considered a peer, break to a different level when he did a song [It’s Only Love on 1984’s Reckless album] with Tina Turner. I’d had four songs that had made the charts, none had the world on fire, but we were doing okay.

So I was like: “Wait a minute, let’s write a song for someone else.” I asked our A&R guy Derek Shulman, who was formerly the singer with Gentle Giant: “How do you go about this?” He says: “Adams is writing with a guy named Jim Vallance.” I say: “Well, do you know people that do this?” He says: “I know a guy”, and mentioned Desmond Child.

Now remember, Desmond Child’s only song at that time was [Kiss’s ‘disco’ single] I Was Made For Loving You. He had two records of his own, which didn’t do anything, but I knew his picture, because right outside the door of The Fast Lane dressing room there was a photo of a guy who looked like David Bryan, with curly blond hair, and three chicks. So we write [You Give Love A] Bad Name. All of us go: “This is too good to give to Loverboy.” And a relationship began, and it changed all of our lives.

Is it true that Desmond Child and Richie literally begged you on their knees to record Living On A Prayer, because you didn’t think it was all that special?

That’s a bit exaggerated. I was like: “Oh, it’s good, but…” To me, Bad Name had more of the anthemic, radio-friendly sound of the time, like Joan Jett’s cover of I Love Rock ’N’ Roll, or Robert Palmer’s Addicted To Love, or Twisted Sister’s We’re Not Gonna Take It. And I was like: “We need that.” And you couldn’t have heard that in the first demo we did.

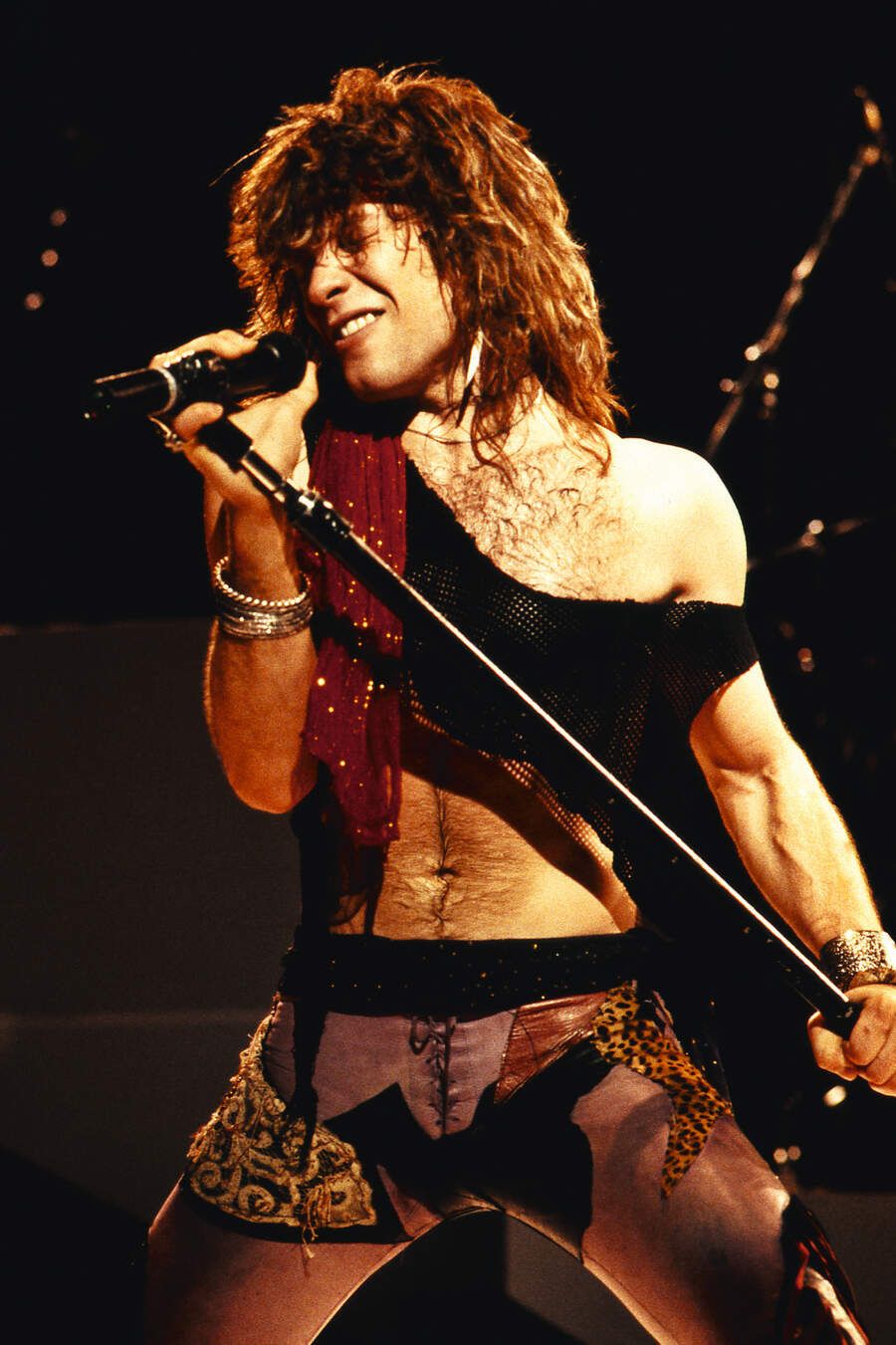

The master stroke, it seemed to me, with Slippery When Wet, was those faked ‘concert’ videos for You Give Love A Bad Name and Living On A Prayer, because: a) the band looked fucking huge, and b) every single teenage boy in the world, this one included, was like: “Look at all those girls at that gig!”

[JBJ gives a thumbs up] Right? Look, if you were lucky enough to learn how to make a record, let alone write a hit song, that was amazing. But now they want to thrust you into this film business? Fuck that. We didn’t know how to make a good video, but by the time we got to that third album we were smart enough to know that: a) we were very good live band, and b) we had to capture that on film. If you go back and look for the Silent Night promo twelve-inch, we’ve all got our fingers up to our lips, and it says: “The best-kept secret in rock and roll.” Now it was time to let everyone in on that secret.

It worked. Slippery When Wet turned Bon Jovi into the biggest band in the world. Can you remember how that felt?

I remember my parents saying to me: “Now everybody knows your name.” Until then, our parents would tell their friends: “My kid’s in a band, and they have a record deal, and they’re opening for Ratt at the Meadowlands Arena. Would you like to come?” Slippery comes, and that’s the end of supporting anyone ever again in our lives. So that changed everything.

Did you feel like a rock star then?

I felt like a rock star in Raze! [laughs]

Then with New Jersey you did it all over again, and became even bigger. In the documentary, you mention that at that point you could just click your fingers and get anything that you wanted. So, if you’ll excuse my French, what stopped you turning into a bit of a c*nt?

Each other… and New Jersey. And by New Jersey I mean more than just our neighbours, but our upbringing. I realised, touring with those West Coast bands and those arena-rock acts, and being on the same management roster as Mötley Crüe, that that wasn’t what I aspired to be, as a behavioural pattern. We got lumped into that because we looked like the rest of them, as did all the kids in the malls at that time. But that’s when I was very aware of: ‘don’t aspire to that, aspire for more, aspire to be different.’

In Thank You, Goodnight you mention that you were never into rock-star ‘over-indulgence’, because you’d had some bad experiences when you were younger.

Yeah, really naive stuff.

Like what?

Something as innocent as something that was laced into the pot. Because I didn’t have the constitution for it. Which was wonderful, because I wasn’t indulging the way others were. Everyone was doing cocaine at that time. And everything else.

Wasn’t it difficult for you to sit on the sidelines?

No. I could have a few drinks and be happy. And I didn’t feel the need to follow anybody. If that was what was going to endear me to a group of people, I just wasn’t interested.

By the end of the New Jersey tour, in early 1990, everybody in the band was pretty frazzled, and things were fractious. Then you went on to your solo career. Did that feel liberating?

Yes. To get back to the joy of making music, to try to figure out why we were confused, because… [in Bon Jovi] we never had a fight, it wasn’t about money, it wasn’t about girlfriends, it wasn’t about drugs. We were exhausted, physically and mentally. So I go off and do [the soundtrack for Young Guns II [aka Blaze Of Glory], and it was liberating on a number of fronts, because: a) I proved that I knew how to do it, and b) I proved that I knew how to do it again – and not only again, but alone. It also introduced me to acting, which was hugely important to the next chapter of the band’s success.

Did you think, even for a minute or two: “You know what, I’ll stick with going it alone”?

No, I did not. I only ever wanted to be with these guys. But after what is now six-to-seven years of being together twenty-four-seven, it was the same jokes, it was the same stories, it was the same meal, it was the same vacations together. You had every right to be exhausted and burned out and tired of each other. And Doc [McGhee, Bon Jovi’s manager at the time] did us no favours. In retrospect I don’t blame him, but he did us no favours if he was supposed to be the grown-up in the room. He should have said: “You guys are fucking exhausted.” But they didn’t, the collective agents, lawyers, managers.

The band’s next album, in 1992, is Keep The Faith. Grunge has happened by then, even bands like U2 are changing their sound, and you’ve decided to part ways with management and be a DIY band, in a sense. Was that album title a note to self as much as anything else?

Yes, to the collective ‘we’. The audacity of us to tell the grunge world that we’re just going to be independent, that we didn’t want to be a part of the new fashionable thing, that we were going to just evolve, and do our own thing. And for me to convince those four guys that we didn’t need not only Doc, but anyone else, was audacious.

You mentioned your acting career earlier. With that did you enjoy being a novice again, because you’ve walked into this other world where you’re the new kid and you don’t have the chops that other experienced actors do.

Well, I privately studied acting several days a week for two years before I even went to an audition. I didn’t just walk in and have the audacity to say: “I know how to do this.” But what it offered me, and what I brought back to the band… had we not had that, when I jumped off that cliff to self-management and cutting my hair off, was the humility of starting over again, at something else in the arts, with all the experience of super rock stardom.

So those two things made for a very strong thirty-year-old version of me. I could go back to the band and say don’t believe the hype from Slippery, don’t believe the hype of New Jersey, don’t believe that I’m doing anything different because of the success of Blaze of Glory. If we come back, humble and hungry, and all put our fucking hands in and say: “Okay, I get it”, nobody’s gonna believe in us more than we believe in us, and let’s give this a shot.

By the time you started work on What About Now though, in 2012, Richie says he thought the band were getting stale.

I didn’t think so, and the collective we didn’t think so. I personally thought that everything was going incredibly fucking well. And it was never brought up in the room, or in the writing, or in the recording, or during the first twenty shows of that tour.

Obviously on a professional level, his exit mid-tour, on the day of a show in Calgary, threw you a curve ball. On a personal level did it hurt a bit too?

It was a shock. Nobody anticipated it, no one saw it coming. I talked to him the day before, I remember it so well. It was Easter Sunday, 2013, and I was driving through the Lincoln Tunnel as I was talking to him, because I was living in New York, and I was like: “Yeah, I’m feeling great, the album is gonna come in at Number One, see you up there.” He said: “Can I stay home one more day?” “Of course. You want to fly private tomorrow? Sure. Do it. I don’t care. See you up there.” And then the next day the phone rings at three in the afternoon, and, you know… “I can’t go on.”

In the documentary, there’s a moment where the interviewer asks you: “How long did it take you to get over it?” And you say: “I’m still not over it, ten years later.”

Sure. I’m heartbroken.

So what’s to stop you bringing him back now?

How many times have you seen him in the last eleven years?

Well, none. But I was never expecting to run into him, to be fair.

I’ve talked to him twice.

Wow. Why?

[Slowly, as if explaining to a child] He. Quit. The. Band. I swear to Christ there was never a fight, nothing. David and Tico have talked to him once, at the [Rock And Roll] Hall Of Fame induction. He wasn’t kicked out, he quit. And he hasn’t made any great overtures about coming back.

Okay. Because I feel like that’s not the public perception. The public perception is that he’s willing to go back, but…

But what? Life goes on. You have to get your reader to understand just one thing, because I’m as confused as anyone else was. If you or I commit to a job, and you don’t show up for the job, people are going to be let down. The band were let down, that’s something you can assume. Oh, and by the way, there’s also a hundred and twenty guys waiting on a pay cheque on Friday. Oh, and then there’s the fans that travelled to see this band, and bought tickets, hotels, flights. And there’s the promoter that paid us the money to do a hundred shows… You’ve got responsibilities. So we went on. It was that simple.

You mentioned the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction. Your speech there had one of the all-time great intro lines, where you said something like: “I’ve written this speech in my head many times, and sometimes it’s the ‘Thank you’ speech, and sometimes it’s the ‘Fuck you’ speech.” Did it sting that you were overlooked for so long by that institution, or by the Grammys committee?

Getting overlooked for Grammys is almost a badge of honour. The Beatles or Zeppelin or the Stones weren’t getting any, but Beyonce has twenty-seven? They’re not naturally drawn to rock bands. Whatever. And the Hall Of Fame is like an old white man’s club, with a secret ballot. It was a little fiefdom. So no, it didn’t sting that we were overlooked. We’ve had some of the biggest albums of all time, we can live without trophies.

Would you swap the sales of Slippery or New Jersey for the critical acclaim of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska?

No, no, no, no, no, no. Anything that’s happened to us – the good, the bad and the indifferent – all the information that got me here today, I wouldn’t trade that for anything.

In the documentary, you’re very honest about the issues you’ve had with your voice. I saw you at Wembley Stadium in 2019, and, respectfully – you’re Jon Bon Jovi and what do I know? – it didn’t sound good. But later I went back and watched a video from that show on YouTube, with you singing Always, and what struck me was that you were really giving it everything. Everything. You’re quite self-critical, and you know when something’s not as good as it could be. So to do that night after night, going on stage knowing you’re not killing it, isn’t that difficult?

It’s so fucking hard. It’s hardest thing I’ve ever had to deal with. Imagine knowing it’s not working right, and you can’t figure out why. It was tough.

How do you cope with that mentally?

It was fucking tough.

Did you have to do something like see a therapist to talk you through it?

One? [Laughs dryly]. You just have to hold on, and give it your all. So, Wembley 2019. Yes, it wasn’t like it was in 2000 or 1995. Or any of the other times I played in that building. I knew that. I won’t argue with you.

On a more positive note, 2020 was a very brave album, because lyrically it’s the most politicised, or at least the most socially conscious, Bon Jovi album. Tackling subjects such as the murder of George Floyd, or immigration to the US, you must have known you were going to alienate a huge chunk of your fan base.

My job is not to pander. My job was simply to narrate. Artistically, that album was very fulfilling. I’m really proud of it.

To circle back to where we started, some of your lyrics on that album were like lyrics Springsteen might have written.

I take that as a compliment. It’s good songwriting and it’s good storytelling. At that time the world was shut down, and you and I are both home watching television and reading the papers, because that’s all we’ve got, right? And so now I take on the role of narrator. As a songwriter, that’s my job. So I write about George Floyd and I write about covid, and I write about guns, and I write about Trump…

How do you feel about the prospect of that man coming back to power?

You know, my job now is to stay out of the way and pray. It will be up to the electorate. I can only pray for the future of the world.

On the new Bon Jovi album Forever, there’s a really good line on the song Seeds, where you sing: ‘You don’t have to fix what is broken, you only get better at coping’, which is a very mature kind of reflection.

Yeah. We’ve talked today about the various obstacles I’ve faced, but all these punches in the face that you take are what gets you to where you are.

And where you are now? Are you as happy now as you’ve ever been?

Am I happy? I’m very content with where I am in my life. It’s all part of the journey. I’m definitely not the guy I was at twenty or thirty or forty, or even fifty. It all changes. I’m here as the Ghost Of Christmas Future to tell you that it all changes. So am I happy? Yeah, I’m really happy. In Legendary I sing: ‘I got what I want, because I got what I need.’ Which sounds simple, but it resonates. I’m talking about your family, your friends, God willing, your health, and that’s a full-circle moment that I couldn’t have said when I was twenty or thirty or forty. Where am I now? I found joy.

Speaking of statements, and of full circles, God forbid that a music journalist would read something into something that doesn’t exist, but the combination of an album called Forever, and a career-spanning documentary titled Thank You, Goodnight, would seem to be the things one might write before writing The End. I hope that’s not the case.

And it’s not my intention. If it was to be the case, it’s not a bad way to exit. Forever is a really strong album, and it’s full of energy and joy and love from start to finish.

Still got it, right?

Still got it.

Forever is out now via EMI. Thank You, Goodnight is available now on Hulu in the US and Disney+ in the UK.

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Source link