Sheryl Crow interview: A lifetime of battles, triu…

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

It’s difficult to believe we’ve had the pleasure of Sheryl Crow’s company for three decades now – not least to the singer-songwriter herself. “I’ll be honest with you, I don’t know if anybody ever really feels their age,” she considers. “I mean, I’m sixty-two and I need to get my lips done, I need to get a little facelift. But unless I’m looking in a mirror, mentally I feel like I’m about thirty-six.”

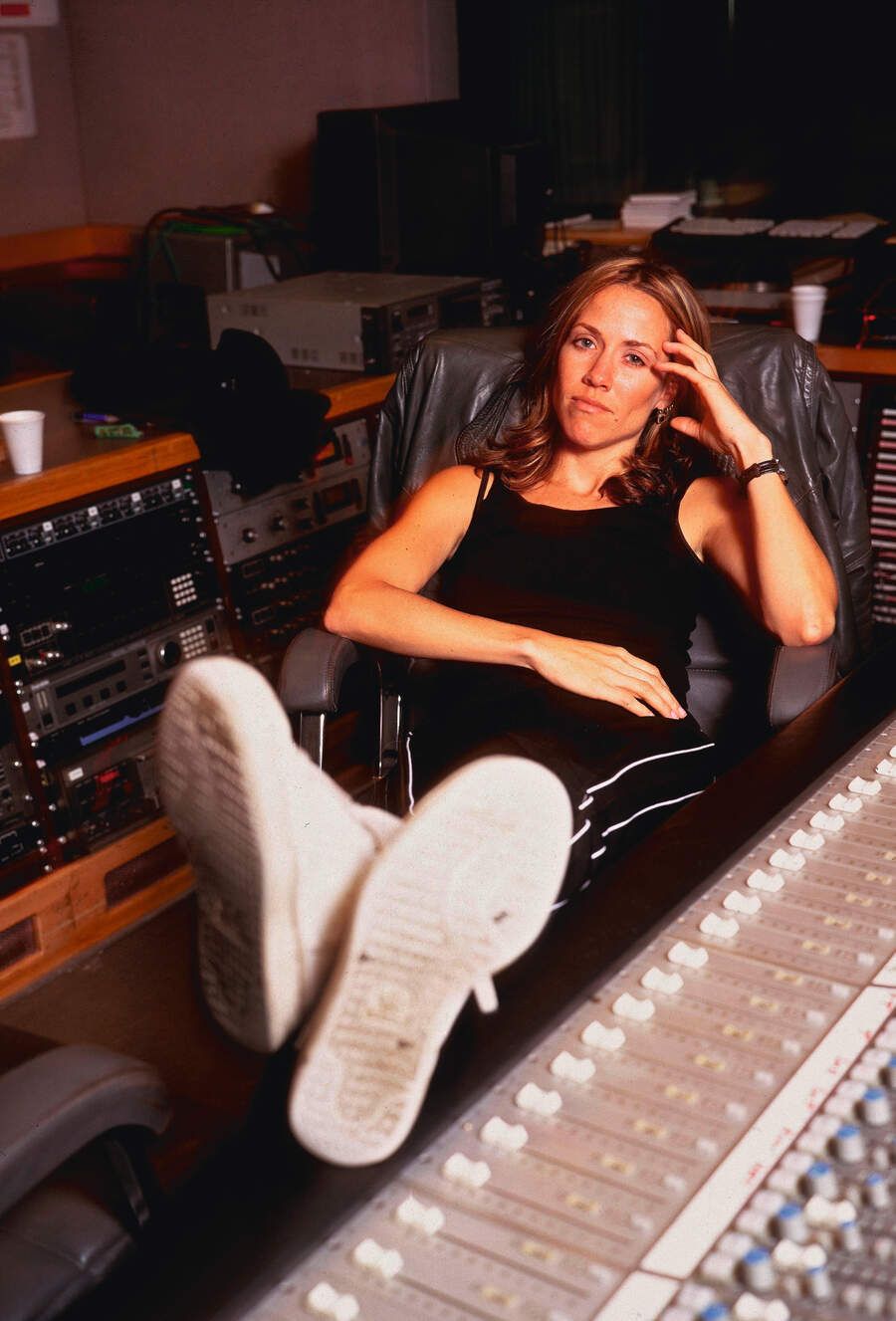

Talking in the music room of her home in rural Nashville, sitting in front of a rack of vintage acoustic guitars befitting the queen of heartland roots rock, Crow is everything we need right now from our rock stars. Witty, articulate, informed and inquisitive, she is nobody’s vacuous pin-up. She has opinions: on gun control, climate change, military conflict, the Presidential election, the insidious rise of AI and what it might mean for her two teenage sons.

Ask her and she’ll talk about all of it (the only subjects we’re told are off the table today are her shift in the 80s singing backing vocals for Michael Jackson’s Bad tour, and her much-raked-over split from disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong). That readiness to stand up and be counted came from her formative years, she says, still talking with a Midwest drawl.

Sheryl Crow was born on February 11, 1962 in Kennett, the largest city of the so-called Missouri Bootheel. A classic overachieving middle child, her prolific contribution to life at Kennett High School saw her compete as an all-state track athlete and join the National Honor Society. But it was the combination of her parents’ politics and her musical talents that set her path.

Your biog makes you sound like the dream teenager – sporty, clever, popular…

Oh, I was perfect [laughs]. No, I was a people pleaser. I think I wanted my parents to really like me. It was all about making good grades, being in student council and the Honor Society. I felt like love was attached to being good, being smart, being liked. Years of therapy had to un-ingrain [the idea] that love is not attached to anything. That everybody deserves to be loved, whether or not you get Fs in school and smoke weed. That love is not something you earn.

And I don’t fault my parents for that. I took on that persona and I ran with it until I was famous. At a certain point, you realise: “Wait a minute, I can stand up here in front of a hundred and eighty thousand people at a festival and walk away not feeling loved. What’s wrong with me? Do I not feel like I’m deserving?” So I was a good kid. But then when I hit my thirties I let it all hang out. I’d been a pretty good girl up until then – then the partying started.

Looking back now, how would you describe your parents?

They were musical and they played together in a swing band on the weekends. I think my dad really would have liked to have been a professional musician, but he got his degree in law and he was a very Atticus Finch [figure], very much about the judicial system. My mom was always an activist. When I was growing up in the late sixties there was a lot of racial and social unrest, and she’d be active in church and taking care of older people.

I think you model to your kids how you see the world, and that was so much in my DNA. My dad was a conservative and my mom was a liberal, so I grew up with them having strong debates about politics. That also informed me about the way the world should look.

As a kid, when did it become obvious that music would be your road?

I have vivid memories of my mom and dad having friends over. They’d be drinking and they’d be like: “Come here and play that James Taylor song for everybody!” And I’d be like: “Ah, I don’t wanna do that!” I can actually remember playing My Love by Paul McCartney – and my dad being so angry. That was my first bit of censorship. He’s like: “Do you know what that song means, young lady?” And I was like: “No, I don’t know what it means, dad – I’m twelve.” I remember being the sort of party trick as a kid. Y’know, bring her out and have her play something on piano.

When did the wider world realise that you had a talent?

When I got to the University Of Missouri and started playing keyboards in bands, I started getting noticed more. But I did not ever want to be Crow a frontperson. I remember my college professor saying that I was never going to be a great classical pianist, because I could play pieces by ear. He said: “You will be a great pop player, but you will never make it in the classical world.” And I knew that. I knew the dedication it took to be a concert pianist was definitely squashed by the fact I could play the piece relatively okay after hearing it a few times.

Even after graduating college, there was no indication of the heights to come, with Crow working as a music teacher, gigging on the weekends and recording a string of sometimes banal but often lucrative advertising jingles. By 1987, it seemed her best hope might be fame by association, with Michael Jackson’s Bad tour seeing her duet with him on I Just Can’t Stop Loving You.

But, as she remembers today, Crow craved a career on her own terms. She moved to Los Angeles in her late twenties to shop her material around, before falling in with the West Coast songwriting collective who performed on (and inspired the name of) her 1993 solo debut Tuesday Night Music Club.

You worked on some advertising jingles. Which was the strangest one you did?

One of the very first things [jingles] I did was for McDonald’s, and I had to impersonate a singing cow. I had to do several different voices, singing ‘Ee-i-ee-i-o’. It was for a campaign where you’d get a toy farm animal with the Happy Meal.

Why do you think you weren’t satisfied just being a jobbing musician?

I don’t know if I was dissatisfied. I think I just always had a burning desire to be [more]. And I’m sure it has to do with my upbringing. I grew up listening to artists who for me were important. I remember listening to great songwriters and rock stars, from Fleetwood Mac to Stevie Wonder, James Taylor, Carole King, Elton John, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell. That’s what I wanted to be. I wanted to write important things, and I wanted to be important. I didn’t want to just be good – I wanted to write music that mattered. Everything else was just something that led up to that.

How did you feel as a newcomer in Los Angeles when you moved there?

The first thing I did was pick up a Thomas Guide map and get a book of all the studios in the greater Los Angeles area. Then I took my demo tape to every single one and said will you please ask whoever to listen to this. I was very naïve. The city looked giant to me. I’d only been there once before. Suddenly I’m there, driving my own car, I don’t know where anything is, I don’t know anybody.

It felt huge and glamorous and full of rich people. I’d never seen Rolls Royces and Mercedes before. I’d see these huge homes everywhere, then I went and crawled into my tiny studio apartment. Once you’re there for a while, the chasm between the wealthy and very-not-wealthy becomes not only overwhelming but really depressing. But I mean, I just figured it out.

Every artist has horror stories of being rejected by record labels. Did that happen to you, and what reasons did they give?

Oh, after I came off the Michael Jackson tour I played for everybody. I think, because of the notoriety of that tour, everybody was hoping I was going to be Madonna or Paula Abdul. And I didn’t want to be those. I wanted to be more like Stevie Nicks or Linda Ronstadt, and that wasn’t what was ‘it’. So I got a lot of development deal offers, but everybody turned me down.

Finally you got signed to A&M Records. But in 1992 your debut album was shelved. How devastating was that for a young artist?

Well it wasn’t devastating, because I didn’t want them to put it out. I was the one who went to them and said: “I feel like this isn’t the right record. I have one shot, and if this comes out, then I’ll be done.” To A&M’s credit, they did not put it out – they ate the four hundred thousand dollars. But I sat around for quite a long time, and started hearing that I was about to be dropped.

And at that time I fell in with Bill Bottrell, and started making the Tuesday Night Music Club record. By the time I made that first record I was twenty-eight. Y’know, I can remember the Rolling Stones saying to me: “If you’re thirty-five in rock’n’roll, you’re not in rock’n’roll any more”.

Do you remember the first time you performed live under your own name?

It was at this club just south of LA. I was opening for John Hiatt, who was pretty big at the time. Even though I had a band, and I’d been playing some gigs, this was the first full-length gig. I invited the guys from the Tuesday Night Music Club to come sit in. And we were terrible – and John Hiatt was so mad. It was like a party. Everybody was drinking and talking on stage, when I was supposed to be opening up for this other artist. After that I was like: “Okay, I gotta get my shit together.”

We think of Tuesday Night Music Club now as a smash hit, but it wasn’t an immediate success. It took the All I Wanna Do single to light the fuse.

It was fantastic when that record exploded, but it was very arduous up to that point. Because we had been touring in a van, and we had travelled everywhere. The first two places that ever played the record were Colorado and France, so it seemed like we were either in Colorado or France at all times.

Then when we had a full-fledged hit on our hands we had to go out and tour it again. So we had two years on that record. And by the end of touring a record for two years, you really want to shoot yourself in the foot and say: “I’m done.” So when I went in to make the second record [1996’s Sheryl Crow], I was very over the first one.

At the time, I was like: “If I never play these songs again, I’ll be happy.” Nevertheless, the gift of that first record was [incredible]. I’m playing that music still, and very grateful for it. I think about a song like All I Wanna Do – which for years I just dreaded playing – and in hindsight there was a moment where I could look at that song as being attached to the infinite opportunities it brought me. When that thing took off, we toured in Japan, Singapore, Russia, Israel – and they knew every word, even if they didn’t speak English. And what can do that? A song can.

From the mid-90s into the early millennium, Crow was a stone-cold superstar, releasing a stream of multiplatinum records including Sheryl Crow (1996), The Globe Sessions (1998) and C’mon, C’mon (2002). A lesser artist might have kept their head down and enjoyed the success, but Crow was already airing her political views – and suffering the fallout, while struggling with an unregulated tabloid press.

That second album caused controversy because of a line from Love Is A Good Thing: ‘Watch our children while they kill each other, with a gun they bought at Walmart discount stores.’ Do you think artists have a duty to speak up politically?

I don’t think they have a duty. I do miss that you can’t do it any more because you have to be concerned about your following. Certainly, when I was coming up in the business, I didn’t have a physical documentation of losing fans, or hearing how much they hated me. And there was a gift in that, certainly. But I grew up listening to great writers who wrote songs that got played on the radio that were about stuff. From Buffalo Springfield to Marvin Gaye, I mean, these were big hits and they were antiwar, they were about race relationships. I miss that.

Almost any song I hear on the radio now is about sex, at least in the pop world. And then in country you hear this false narrative about America. I’m just like: “Where are the truthtellers?” Well, they’re probably not gonna get played on the radio, and I don’t know if they’re gonna ‘trend’ anywhere. I don’t know how any of that works any more. But to me, writing is my safe place, it’s my therapy, it’s my love, it’s my release.

Your performance at the ill-fated Woodstock 1999 festival was soured by sexist cat-calls from the crowd. What do you remember about that day?

I have jarring memories of it. It’s funny, you can have an amazing gig and remember very little about it. And when I say it was a shit gig, they were literally throwing faecal matter from the porta-potties they’d turned over. And it was a very sexist atmosphere. It was a debacle.

Watching the documentary [Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99], you realise: “Okay, all things that are money-driven are going to wind up being a shit-show.” Everything is about intention. If you start out with the intention being bringing people together in the spirit of Woodstock, it would have been a completely different scenario. They got what they got.

Which tracks from your first few albums would you put on a jukebox?

Oh gosh. Maybe the obscure songs. I think every artist wants to play the song that tells the tale of their parts – and those are generally not the hits. I mean, I’d say that My Favourite Mistake, from The Globe Sessions, would be on the jukebox, because I still enjoy playing that song and hearing it when it comes on the radio.

There’s also a song on that record called Riverwide that is very Appalachian-meets-Zeppelin. I love playing it. But people in the audience kinda look at me like: “What is she doing right now? I’m gonna grab a beer…”

Yeah, I mean, there’s a song on every record where I feel like: “Okay, this is the summation of my existence” – and those are generally the songs where people go to the loo.

Every young band and artist thinks attaining massive success will make all their dreams come true. Is that how you found it?

Oh no, I didn’t find it that way. I found it to be very confusing. Because one day you’re struggling to get on top, then within what feels like a week you’re on top, and then there’s this crazy hysteria to rip you apart. I think if you’re an artist – which already dictates that you’re a pretty sensitive person, at least in my case – I could read a review and it might be glowing, but there might be two negative comments, and those would stick with me far more than any of the accolades.

I think kids now are more able to navigate the fame thing, because they go in to become famous, and then everything serves that purpose. But for me, like I said, I wanted to be great. I wanted to write great music, I wanted to be the best musician I could be, I wanted to be important. And at the end of the day, you realise: “Wait a minute, I need to reassess what this means to me.”

I remember Chrissie Hynde talking to me when I was making the C’mon C’mon record, which was killing me – I’d spent a ton of money on it and just couldn’t seem to finish it. She was like: “Music is not your life, it’s something that you do.” And she told me about taking time off to raise her kids and then coming back. She’s like: “This is something that should give you joy”. It took that moment – and struggling up to that moment – for that to have meaning for me.

You’ve been open about struggling with depression around the turn of the millennium. How bad did things get?

It was pretty bad. For me, there were maybe three occasions where I had to get very tangible, like, stop everything and get help. I’m not ashamed to say it, and I’ve been lucky that I had people around me who were not afraid to ask how they could help, my manager being one of them.

Are you glad social media wasn’t around to document those times?

Honestly, if I had to live in a fish bowl like people do now… I wouldn’t be able to.

Did you experience those kind of intrusive moments that haunt the biggest stars – fans hammering on the car windows and so on?

Yeah. I think the one that illustrates it best, though, was when my high-profile engagement [to Lance Armstrong] broke off in 2006, and six days later I was diagnosed with breast cancer. And the paparazzi were outside, shooting into the house, trying to get me looking forlornly out the window or something. I couldn’t go for a jog in the neighbourhood without them running after me.

At a certain point, it did make me feel like: “Who are we as humans if what sells these magazines that everybody is buying is seeing somebody at their lowest moment?” And it wasn’t long after that that I wound up moving to Nashville. I felt like I could protect myself better there and I could feel better about what life is supposed to hold.

Your collaborators from that period include Prince, Keith Richards, even Johnny Cash. What are your favourite memories?

That would have been the one argument for having a cell phone – all the selfies. Prince was everything you hoped he would be. Larger-than-life. A great hang. A smart guy. Perhaps the finest musician I’ve been around. Y’know, the guy has a basketball court next to his studio – he’s shooting in high heels. We recorded in his studio, and then he’s like: “Let’s go downtown.” We go to First Avenue, and we kick the band off and we play. He was that guy. He was unpredictable. And if he picked you, that was like the height of a compliment. I still listen to his music and get off on it. I’ll still go out and jog to Sign O’ The Times. The guy’s a genius.

Even now, you get the sense that Sheryl Crow is still questing. As a Nashville resident and lifelong fan of artists like Gram Parsons, Emmylou Harris and the Flying Burrito Brothers, her swerve into country music with 2013’s Feels Like Home felt more honest than calculated. But she grew frustrated with country radio’s gatekeepers, and has seemed more comfortable since returning to her roots with 2017’s Be Myself, setting in motion a late-period run that includes this year’s Evolution. It’s a record with heavy themes that you can dance to, we suggest, and Crow doesn’t disagree.

What was the thinking behind having your country period?

I wanted to stretch myself. I also loved the idea of only playing on the weekends, because I had two little baby boys. And that’s what country artists do. But you can’t break into that world, even if your music was inspired by country artists that these young people don’t even know. So it was a great exercise, and I do feel like some of the songs on those records are really well crafted. But it’s not completely authentic to what I do. I think my reaction to that experience was making Be Myself – and literally writing and recording it in three weeks.

You’ve won nine Grammy awards. How much does receiving awards mean to you?

My thirteen-year-old came into the piano room the other day, and on the top shelf are my Grammys. He said: “Mom, you should have a trophy case.” And I was like: “Nah.” Let’s face it, I’ve gotten to stand on stage with Eric Clapton and sing with Johnny Cash. That could not be moulded into a piece of bronze and have as much meaning as being there. At the end of your life, I think it’s the people and the moments, not the awards.

You said that 2019’s Threads would be your last album. How come you’ve just released Evolution?

You can’t believe anything that comes out of my mouth. Everything I’ve said in this interview has been a lie. No, I did say that, and for good reason, in that I do think making an album is, I would say, an overindulgence. But really what I mean is a complete and total waste of time and money. Because people don’t listen to a full body of work, with a beginning, middle and end. This record, though, I had seven songs I sent to Mike [Elizondo, producer], and in the course of that we wrote a couple more, and it was like: “Well, we have an album.” It just felt like a collection.

‘Evolution’ is a fascinating album title. But it doesn’t seem like you’re necessarily happy with the direction that human evolution has taken?

Well, I guess I’m asking the question: where are we going? I’m the mom of two teenagers, and I ask the hard questions. Like, why are we in this position? The planet, environmentally, is in grave danger. We’re in all of these wars. And people seem to hate each other in this country. And then you plop in the middle of all that, the advent of AI. Y’know, that is going to be a part of our every waking moment. And for artists it’s terrifying. So I guess it just asks the question: at what point are we going to return to soul, spirit and truth from lies?

Why do you distrust AI so much?

It’s interesting, because years ago [theoretical physicist] Stephen Hawking predicted that it wouldn’t be the climate that would be the demise of mankind, it would be AI. Well, at the time, I was testifying before Congress about stopping global warming and working on climate change and blah-blah-blah, and I was, like: “AI? I don’t even know what that is.” And we’re here now.

I started reading about it, and thinking this is dangerous territory for artists. Because if you have AI programmes that can write lyrics for you – or you pay five dollars and have John Mayer sing your demo, and you won’t be able to tell the difference – then where are we going?

Obviously, we’ve seen what happened with Taylor Swift. You have to ask at what point are we going to stand up, as a people – fuck politics, our government is not going to do anything about anything. Will we stand up and say: “Wait a minute, this is dangerous?” I mean, it’s one thing to find a cure for cancer using AI, but it’s a different thing to start bringing people back from the dead, like George Carlin, and having Taylor Swift looking like she’s a porn star.

Tom Morello plays the guitar solo on the title track. What was it like working with him?

I love Tom. I’ve known him for years. He is a person who stands up for what he believes in and shows up to causes. He’s just a good dude. We were both inducted at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame this year, so I got to give him a big hug and tell him how much it meant to me. The way he played was his interpretation of what AI looks and feels like. He nailed it. He gave a complete visual and physical feeling of the chaos that will ensue, through his guitar solo. I will be very curious to see if anybody I ever play that song with can nail his guitar solo. I don’t think so!

Which other themes came up for you when making this album?

Well, one of the early things I sent Mike was a song called Broken Record. Right down the street is where the school shooting happened here in Nashville, and I was quite vocal about how it’s time for [stricter] gun legislation. And just the hate, and the death threats, and the vitriol that I received on social media, it was shocking. And that song is a response.

I had reached out to a bunch of country artists and said can we get in a room and talk about where we meet. And I got nothing. So that’s what Broken Record is about. It’s like, people who are sending out Christmas cards with their family holding guns. Why would you want to do that? I feel like the whole record is full of questions. Like: who are we?

It’s election year in the US. Do you have hope?

Errrr… I’m scared. Honestly, there’s just so much to fix. My feeling about where we’re at – and it’s probably true of every country – is that there’s too few making too much money. And that’s what’s running everything. That’s what’s running the narrative. That’s what’s keeping people down, making people believe in a tyrannical candidate. It’s a strange time. It’s almost like we don’t see the fact that the people that are making money – that are doing anything to keep the power – are keeping everybody else down.

The intro to Alarm Clock almost sounds like a teenage garage-punk band. Why do you think you still haven’t mellowed?

That was a fun day. I said: “I want to write about how I hate my alarm clock, because when it goes off, all that beautiful dreaming about floating on a yacht, y’know, it all stops.” Mike banged out this groove and it just fit the song.

One of the beautiful things about making this record was I kinda treated it like a gift that I was giving myself. I didn’t have the grinding of teeth that I usually have when I’m producing or tracking myself. This was like a kid in a garage with a bunch of motorcycles, and: “What shall we throw together to make this thing run?”

I’ve always said that I feel my best work is still in front of me. You have to be able to let go of wanting it to be successful. You reach a certain age, and in this climate, with streaming and everything, you doubt you’ll be heard, and then all the parameters are off. But also, you’ve got all this fire in your belly, and all these things you want to write about, because you’re watching how it affects your kids.

Despite those heavy themes, it doesn’t feel like a doomy record.

Subconsciously I love being able to talk about the reality of being alive – but not make you want to jump out of a window. Even a song like All I Wanna Do, which was dressed up with the most fun Stealers-Wheel-meets-Marvin-Gaye [sound], is pretty sardonic. And that’s good. It’s good to have all things be a part of the trip through the lyric.

Could you have been anything else, in a parallel universe?

I’m not built that way. I love the idea of parallel universes, I’m open to any crazy, cosmic, mind-blowing theory. But I guess one of the reasons I don’t think in that context is because I don’t feel like I’m very good at anything else. I’m not a great cook. I don’t think I’d be a great wife… I get bored too easy.

Who do you think is a great model for a late-period career?

Well, Bonnie Raitt won the biggest award at the Grammys last year. That’s a great career. Emmylou Harris, when she did that Daniel Lanois record [Wrecking Ball] and the two records after that, I was just like: “Woman! Your writing now is just incredible.” I was like: “Y’all give me hope that there’s no reason to stop just because you’re over forty, over fifty, or even over sixty.” Touring-wise I’m gonna keep going as long as I can. There is the pitfall of who wants to come see a seventy-year-old woman perform. But people want to see Madonna. So I don’t know. I just try not to limit my thinking.

When you look back on your career, have you had some fun?

I’ve had the most fun. I’ve had some of the funnest evenings, the funnest early mornings. All of it. I feel like I’ve had several different lives. Y’know, there was the Hollywood period where I would have tons of parties at my house, with people like Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, the Rolling Stones and John Travolta. I look back at that and I go: “Who was that person?” And now I’m raising two boys, and we laugh and play disco music while we’re cooking. That is what I call the infinite possibility of life.

Evolution is available now via Big Machine.

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Source link