With The Works, Queen returned to their rock roots…

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

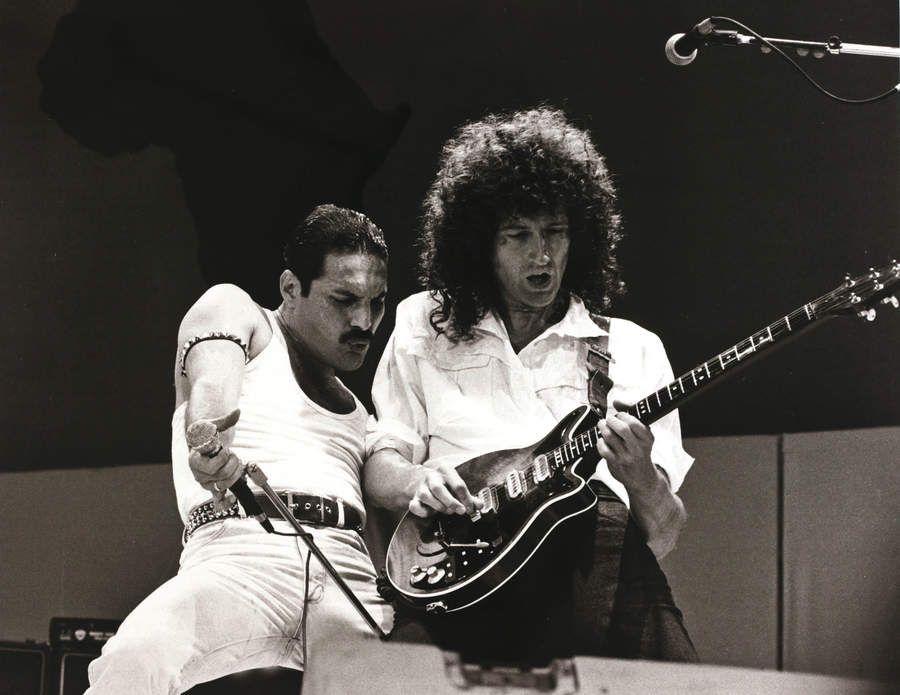

“Here’s one for all you heavy metal fans to have a good jerk-off to,” Freddie Mercury said to the audience gathered inside Auckland’s Mount Smart Stadium. On cue, Brian May struck up the riff to Hammer To Fall – and hoped the singer would remember the words to it.

It was April 13, 1985, during the final leg of Queen’s The Works tour, and Mercury was, in his own words, “fucking pissed”. Pop dandies Spandau Ballet were having a day off on their New Zealand tour, and earlier in the day vocalist Tony Hadley had gatecrashed Queen’s sound-check. Mercury spirited him away for “a little drinkie”. One bottle of Stolichnaya vodka and another of vintage port later, and it was show time.

Just before going on stage, Mercury was so inebriated he had to lie on the dressing-room sofa while a couple of aides laced up his boxing boots. When he staggered to his feet, he realised they’d put his tights on back-to-front. “Oh you stupid c**ts,” he hissed, as Queen’s intro music began playing over the PA. The minions frantically removed his footwear and leggings, and Mercury bounded on stage just in time.

Performing drunk was a rare lapse of judgement. Either that, or a cathartic release at the end of a challenging tour. Queen’s eleventh album, The Works, had been a UK No.2 hit, but had flatlined in America; their videos weren’t being shown on MTV; the group had been blacklisted for performing in apartheid South Africa, and were booed in Rio de Janeiro.

The Works delivered four solid gold hits: Radio Ga Ga, I Want To Break Free, It’s A Hard Life and Hammer To Fall. But before their show-stopping appearance at Live Aid in the summer of 1985, Queen were in disarray. “By the end of The Works we all needed a break,” May admitted. Drummer Roger Taylor insisted: “We hadn’t broken up, but we didn’t know what was coming next.”

Mercury’s remark about “heavy metal fans” was a glimpse into his present mindset. He was about to release his debut solo album, Mr Bad Guy, which was filled with the sort of dance music he heard in the clubs around his adopted home cities of New York and Munich.

Mercury was no longer swanning around in a satin jumpsuit, singing about ‘the mighty titan and his troubadours’. Now sporting the short hair and thick moustache on trend in the gay community, he was also smuggling his nouveau influences into Queen.

The group’s 1980 album The Game had dialled down on their usual grandiloquent hard rock, while 1982’s Hot Space was such a departure that it confused their fan base – and some of the band. Brian May struggled to have his guitar heard on the R&B tracks Body Language and Staying Power. And his reduced role in the Queen/David Bowie love-in Under Pressure has niggled him for decades. “One of these days I would like to remix it,” May has said, repeatedly.

However, Hot Space’s modest chart placing and the subsequent tour’s weaker ticket sales had knocked Queen’s confidence. “Hot Space got us out of our comfort zone but was probably a step too far,” admitted May, who took himself off to Los Angeles to make Star Fleet Project, a mini-album, with fellow guitar hero Eddie Van Halen and heavy friends.

“Hot Space wasn’t really us, was it?” ventured Taylor, who was soon busy with his second solo album, Strange Frontier. Then Queen received a proposal. Director Tony Richardson was making a film of John Irving’s novel The Hotel New Hampshire, a tale of a dysfunctional family blighted by suicide and incest. Would Queen score the soundtrack?

In July 1983, Mercury and bass guitarist John Deacon met Richardson in Los Angeles, and booked the Record Plant studio for a month’s time. The rest of Queen and producer Reinhold Mack (known simply as ‘Mack’) joined them soon after. The decision to go back to work couldn’t have come quick enough for Deacon, the only Queen member who didn’t have a solo record deal. “I went spare, because we were doing so little,” he admitted. “I got bored and quite depressed.”

There were business factors involved too. Mercury refused to record for Queen’s US label, Elektra, whom he blamed for Hot Space’s commercial failure. “Freddie was so depressed about the situation, it was doubtful he would have agreed to make a new Queen album,” said May.

Queen’s business manager, Jim Beach, paid to release Queen from Elektra before signing them to Capitol in the US. It was enough to persuade Mercury back into the studio. Tasked with recording a soundtrack and a new album, Queen hoped that recording in Los Angeles rather than Munich’s Musicland Studios (where they’d made The Game and Hot Space) would focus their minds.

“We’d all become emotionally disconnected in Munich,” May explained; a discreet way of saying the nightlife had impacted on their work, their marriages and even their sanity. However, before long, Rod Stewart and Jeff Beck were dropping by the Record Plant for an all-night jam, while the nearby Coronet Pub and Osko’s, a disco famed for its female mud-wrestling nights, exerted a magnetic pull on band and crew members alike.

Soon, most of the retinue were tooling around town in rented sports cars. Mercury moved into Elizabeth Taylor’s old residence, a dazzling pink villa in Bel Air, which he filled with hundreds of dollars’ worth of flowers. On one of his many nights out in West Hollywood, Mercury met a biker known as ‘Vince The Barman’, and moved him into the property. Vince became the object of Mercury’s affections and the recipient of many lavish gifts.

“The accountant was on the phone every day,” recalled Mack. “He’d never seen people burn through as much money as we did. Soon after we arrived in LA he was asking questions like: ‘Why do you have nineteen rental cars when there are only eight of you?’”

For the first time, Queen also invited an outsider into the sessions: Fred Mandel, a Canadian musician who’d previously played keyboards on the US leg of the Hot Space tour. “I was making a record with Alice Cooper [Flush The Fashion],” recalled Mandel. “[Queen’s old producer] Roy Thomas Baker was producing, and recommended me to Queen.”

However, Queen’s working methods had changed since Baker’s day. “You’d have two of them in one studio and two in another working on different songs,” explained Mack. “The last time the four of them were all in the studio at the same time was The Game. Now everyone was on different schedules.”

Accommodating four writers became a greater challenge with each album. Queen brought around 20 songs to the sessions, and the editing process was brutal. Several of Taylor’s songs were rejected. However, the rejection helped Taylor raise his game. Queen had abandoned their previous ‘No Synthesisers’ policy. Taylor was using both a synth and a drum machine on a new piece of music with May. The guitarist kept his part for another song, Machines (Or Back To Humans), and Taylor used his for what became Radio Ga Ga. But it was a happy accident: “I couldn’t have written the song on a guitar. I don’t want to know about anything technical – like what the chords are called.”

It was Mercury who spotted the song’s potential. Before Taylor left for a skiing holiday, he gave Mercury his blessing to do as he wished with Radio Ga Ga. “I felt there were some construction elements that were wrong,” said Mercury, “so I took the song over”. The song’s title was inspired by Taylor and his French partner Dominique Beyrand’s toddler son Felix, who murmured “ca ca” (Taylor: “French for something that comes out of your bottom”) while hearing an unnamed song on the radio.

Mercury changed the words to ‘ga ga’, on a song mourning a lost, bygone age of radio. When Capitol Records president Jim Mazza heard it, he sent a telex to Queen’s management, worried that the lyrics would alienate the radio networks. Mazza asked if they could be tweaked to become “a supportive endorsement of radio’s future rather than a prediction of its demise”. Queen never divulged whether they changed the words. But it was an early indication of the group’s difficult relationship with Capitol, and America as a whole. It would only get worse.

Freddie Mercury famously described Queen as “four cocks fighting”. When the conflict became too much, Mack sought refuge in a bar across the road from the Record Plant: “It was somewhere for me and John Deacon to get some peace and quiet.”

The producer’s Zen-like calm defused some of the tension, and Fred Mandel maintained a Swiss-style neutrality during band arguments. “Queen were rational, intelligent guys,” the keyboard player explained. “When they came together they were like the four musketeers, but there were disagreements. I’m not saying they weren’t rock’n’roll, but they weren’t Guns N’ Roses, arguing about downing a fifth of Jack. They were more likely to be arguing about the wingspan of a butterfly.”

“Oh, we argued about everything,” May concurred. “But it was usually for the good of the music. We all believed passionately in what we were doing.”

Unfortunately for May, this meant being sidelined on one of The Works’ biggest hits. Mack nicknamed John Deacon ‘The Ostrich’, because of his ability to remain silent for long periods of time before “laying the perfect egg”.

By 1983, Deacon had laid two with the UK and US hits You’re My Best Friend and Another One Bites The Dust and was about to deliver another, I Want To Break Free. However, Deacon, rather than May, played acoustic guitar on the song, and Mandel played the solo on his Roland Jupiter-8 synthesiser.

“John didn’t want a guitar solo on the song,” Taylor explained. “So he got Fred [Mandel] to improvise something around the main tune.”

“This was controversial,” Mandel admitted, “as apparently no one did solos apart from Brian. But I didn’t think anything of it, as I’d done the same on Alice Cooper records. It was no big deal, but people thought it was a big deal.”

Tellingly, May’s guitar was added to the intro in the single mix.

After two months in LA, film director Tony Richardson announced that his budget couldn’t stretch to Queen, and he’d have to use existing music instead. The band repurposed some of their The Hotel New Hampshire material for The Works, but decided it would be more cost effective to finish the album in Munich.

Not everyone would be joining them, though. Vince The Barman turned down Mercury’s offer to leave LA, bringing their relationship to a sudden end. Mercury drifted into the Record Plant looking downcast. After sitting quietly for a time, he suddenly exploded. “It’s okay for all of you!” he shouted at anyone in earshot. “You all have your wives and families. I can never be happy.”

Mercury would explore these emotions in another new song, It’s A Hard Life. “It’s one of the most beautiful songs Freddie ever wrote,” suggested May, “and he really opened up during the creation of it.”

In Munich, though, everybody returned to their old haunts and habits. The proprietor of the Sugar Shack discotheque (immortalised in the Queen song Dragon Attack) welcomed them back with a bottle of their usual tipple, Moskovskaya vodka, and Mercury wrecked the ligaments in his knee during drunken high jinks in the city’s New York bar. One day, after a bad bout of musical differences, May left Queen and spent a few hours pondering his future in a park in central Munich before deciding to carry on.

The feeling was contagious. John Deacon quit for an impromptu holiday in Bali, but told only his bass tech that he was going. When Mercury heard the news, he jumped on a studio table and began crooning Bali Ha’i from the musical South Pacific.

When Deacon returned, the sessions continued as before. The only difference was the bass player’s sunburnt skin flaking off over the mixing desk, prompting Mercury to nickname him ‘Snakeman’. “We were okay about Deaky going to Bali,” recalled May, “because we were all going mad as well.”

The world received its first taste of The Works when Radio Ga Ga was released as a single in January 1984. The song was credited solely to Taylor, giving him his first UK top-five hit since I’m In Love With My Car, the B-side to Bohemian Rhapsody in 1975.

In typically contrary style, Queen had hired David Mallet to direct a video (which eventually cost £110,000) promoting a song moaning about the dominance of video. But Queen were nothing if not pragmatic.

Mercury and producer Giorgio Moroder were dabbling with the soundtrack for a new version of Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi movie Metropolis. Lang’s footage of industrial cogs and smoke-belching chimneys was stripped into Mallet’s film, which showed Queen zooming around in a flying car, and conducting 500 extras in a synchronised handclap. This part was supposed to illustrate how modern radio’s meaningless ‘ga ga’ had turned listeners into gormless drones. But some critics compared the scene to a Nazi party rally. “People thought we were really trying to be dictators,” May grumbled. None of this mattered when Radio Ga Ga became a UK No.2 hit.

But the single tanked in America. At the time, many record labels used independent pluggers to secure radio airplay with clandestine payments. Now an industry-wide investigation was under way, and the labels panicked.

“So Capitol got rid of all their independent guys,” May explained, “and the reprisal from the networks was aimed at the artists who had records out. Radio Ga Ga was rising, but the week after that it disappeared.”

However, Queen’s dealings with American radio had become problematic around the time of Hot Space. For years, May refused to name Mercury’s personal manager, Paul Prenter, in interviews, referring to him only as “the guy who looked after Fred”. This was no longer possible after the Bohemian Rhapsody movie. Here, Prenter (played by actor Allen Leach) was reborn as a classic movie villain who drove a wedge between Mercury and Queen.

“It wasn’t far off the truth,” said May. “He was very dismissive with the radio stations. “I discovered later that he went around saying: ‘No, Freddie doesn’t want to talk to you.’”

“Prenter was always whispering in Freddie’s ear,” confirmed Mack. “They were both into R&B and disco, so you had Prenter telling Freddie that Queen were old-fashioned and he didn’t need guitars.”

However, The Works (named after another of Mercury’s favourite clubs and his pre-tour rallying cry: “Give ’em the fucking works!”) was unlike Hot Space. Released in February 1984, it was a belting rock album cunningly spliced with pop songs and ballads.

Mercury’s compositions ranged from the inspired to the throwaway. His courtly ballad It’s A Hard Life lived up to May’s praise, while Man On The Prowl was rockabilly-by-numbers redeemed by Fred Mandel’s honky-tonk piano. Keep Passing The Open Windows (titled after the family’s catchphrase in The Hotel New Hampshire) had a maddening chorus, and lyrics straight out of Mercury’s self-empowerment handbook (‘You just gotta be strong and believe in yourself…’). Is This The World We Created…? was written at the last minute to provide a Love Of My Life-type ballad.

May and Taylor shared the credits on Machines (Or Back To Humans), a mash-up of synthesiser, Vocoder and howling guitar, with now-dated lyrics about ‘bytes and megachips’, and May scored with two blood-and-guts rockers: Tear It Up and Hammer To Fall, the latter using the catchiest of hooks to warn listeners that we were all doomed if Reagan or Chernenko started World War III.

The Works reached No.2 in the UK and No.23 in the States. The numbers would have been better had Queen toured America. “But Freddie didn’t want to go back and play smaller venues,” said May. “He was like: ‘Let’s just wait and then soon we’ll go out and do stadiums as well.’”

However, Queen were about to scupper their chances further. A second single, I Want To Break Free, became a UK No.3 hit, accompanied by a hilarious but problematic video. A pastiche of the British soap opera Coronation Street was always going to be a bit parochial, but Queen appearing in drag was too much for MTV. Two decades later, Dave Grohl dressed as several women in the promo for the Foo Fighters’ Learn To Fly. But when Queen did it 40 years ago, MTV refused to use their video.

“For the first time in our lives we were taking the mickey out of ourselves,” Mercury protested. “But in America they said: ‘What are our idols doing dressing up in frocks?’”

“MTV hated it,” said May. “They could not accept a rock group dressing as women, and in America Queen were still seen as a rock group.”

Then again, it was difficult to imagine Eddie Van Halen modelling May’s pink nightdress and hair curlers, nor even Dave Lee Roth wearing fake breasts and pushing a vacuum cleaner, à la Freddie. So convincing was Roger Taylor’s schoolgirl that David Mallet’s fiancée spotted him and Taylor in a huddle and thought they were having an affair.

“I’m Canadian, so I got it,” recalled Fred Mandel. “I mean, come on, it’s just Benny Hill, typical British humour. I also liked seeing Roger doing the dishes and Freddie doing housework.”

Capitol pleaded with Queen to make an alternative performance video for MTV, but Mercury refused. There was no persuading him, something May found frustrating while shooting a promotional clip for the next single, It’s A Hard Life. May applauded Mercury’s willingness to address his emotional turmoil in the song: “And then he went and dressed as a giant prawn in the video. I was terribly disappointed.”

Mercury, in his prawn-like ensemble, roamed a Bacchanalian wonderland populated by cross-dressing ballerinas and extras in ball gowns and insect heads. Partway through, Taylor and Deacon sloped into view wearing tights and Elizabethan ruffs (with the drummer’s late 20th-century baseball boots visible in one shot).

It’s A Hard Life was another UK Top 10 hit, while the next single, Hammer To Fall, reached No.13. Both cued up Queen’s world tour, albeit minus America. “There were always other places for us to go where we were selling well,” suggested May. Regrettably, these included South Africa, where I Want To Break Free had gone to No.1.

In October, Queen defied the United Nations’ anti-apartheid boycott to play Sun City, a hotel/ casino complex in Bophuthatswana. They’d been informed that racial segregation didn’t apply there. Which was nonsense. With tickets costing the equivalent of more than £50 each in South African rand, Queen performed to a sea of white faces in a wealthy white person’s playground.

The band received a Musicians Union fine and were placed on the United Nations blacklist. “Queen are jerks,” declared Daryl Hall, of soft-rock duo Hall And Oates, and one of the Artists United Against Apartheid collective.

“We thought we could build bridges,” May said.“We are totally and fundamentally opposed to apartheid.”

“On balance, going there was a mistake,” conceded Taylor.

Mercury, who was born in Zanzibar, in the Indian Ocean off the coast of East Africa, never ventured an opinion.

A month after their ill-fated trip to South Africa, Queen released a non-album single, Thank God It’s Christmas. The title sounded like a collective sigh of relief. But it was eclipsed by Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas?, a charity single from which Queen were noticeably absent. “I don’t know if they would have had me on the record,” suggested Mercury. “I’m a bit old.”

In the pre-internet world, it took longer for bands to discover where and why their records were selling. I Want To Break Free had been a hit in South Africa because it resonated with supporters of the anti-apartheid African National Congress movement, whose future president, Nelson Mandela, had already spent more than 20 years in prison.

By January 1985, the song had been adopted as a protest anthem in Brazil. After two decades of military dictatorship, the country was about to hold its first democratic election since 1964. Mercury’s impassioned ‘God knows I want to break free!’ spoke to the country’s oppressed, meaning that this most apolitical of rock groups had accidentally become political.

That month, Queen arrived in Brazil to play the opening and closing nights of the 10-day Rock In Rio festival at the Barra Da Tijuca stadium in Rio de Janeiro, the biggest rock festival ever held, with a reported attendance of 1.5 million. By now Queen were at the peak of their live powers, and Mercury saw no reason to adapt their show.

After a victory lap of Crazy Little Thing Called Love, Bohemian Rhapsody and Radio Ga Ga, Queen returned to encore with I Want To Break Free. Mercury strode in from the wings sporting a wig, and a tight sweater under which he’d jammed a pair of torpedo-shaped plastic breasts. This was his second pair, as previously European audiences had complained that the first ones weren’t visible from the cheap seats: “So I had to get some bigger tits.”

However, the costume upset the Brazilians, none of whom had seen Queen’s video and couldn’t understand why Mercury would undermine the song’s heartfelt message. Contrary to press reports, they didn’t bombard the stage with bottles, but they booed and jeered, until Mercury removed the offending accessories.

“There was no place Freddie wouldn’t go,” May marvelled, years later. “Even singing with false breasts in South America.”

The Works, its singles and videos summated Queen’s unique place in 80s rock, but also the inner conflict that defined it. “We always wanted to change,” Taylor explained, “and we never regarded ourselves as a singles band. But I’ve come to realise that a lot of people do think of Queen as just that. Or they think that all we did was flounce around in dresses.”

By the time Mercury performed drunk at their show in Auckland, Queen had agreed to take a year off after the tour. “I think that we probably all hated each other for a while,” said May.

In April 1985, Freddie Mercury released his first solo single, the dance track I Was Born To Love You, followed by the album, Mr Bad Guy. The rest of Queen wondered if they’d lost him for good. “Freddie had stepped so far away,” said May. “I thought we might not get him back.”

Then came the request that changed all their lives. Boomtown Rats vocalist Bob Geldof, the brains behind Band Aid, was planning Live Aid, a fundraising concert for famine-stricken Africa. Geldof wanted Queen to play, and wouldn’t take no for an answer.

“We definitely hesitated to say yes,” recalled May. “We had to consider whether we were in good enough shape. The chances of making fools of ourselves were so big.”

They needn’t have worried. During the early evening of July 13, Queen arrived to find 72,000 people inside London’s Wembley Stadium and cameras waiting to broadcast their performance around the world. Mercury trotted on stage like an eager show pony, flashing a knowing grin, like he was about to deliver the punchline to the world’s funniest joke. As he hammered out the opening notes to Bohemian Rhapsody on a grand piano, Queen’s doubts and fears evaporated. For the next 20 minutes they gave the audience ‘the works’ and more. The four musketeers had returned to fight another day.

Magnifico! The A To Z Of Queen by Mark Blake is published by Nine Eight books.

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Source link