“Phil wouldn’t be afraid to throw a punch, but it …

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

In late 1978, now signed to Bronze Records, and with the latest tour completed, Motörhead could get down to two weeks of recording at Roundhouse Studios in London. Whereas Motörhead had been hammered out double-quick in a desperate bid to clinch an LP release with Chiswick Records, the album that became Overkill had a bigger budget and meant ‘Fast’ Eddie Clarke could take his time on his overdubs once the trio had recorded the basic tracks.

Producing was the legendary Jimmy Miller, who’d made his name at Island before helming the Rolling Stones’ late-60s and early-70s ‘purple patch’. His dad had run a New Jersey club favoured by the Rat Pack, and brought Elvis to Las Vegas in 1969. Miller had trained in studio engineering as a protégé of Stanley Borden, the owner of US labels RKO, After Hours and Unique Jazz, who was Chris Blackwell’s original backer in Island Records. After Borden suggested bringing Miller over to the UK, he swiftly established himself producing hits for the Spencer Davis Group, including Gimme Some Lovin’, and I’m A Man which he co-wrote with Steve Winwood.

Miller went on to work on big late-60s albums by Spooky Tooth, Traffic, Blind Faith and Delaney & Bonnie before ’68’s Beggars Banquet marked the start of his studio relationship with the Stones, which continued with Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, Exile On Main St and Goats Head Soup. Miller could also play percussion, and did the cowbell intro to Honky Tonk Women and played drums on several tracks when Charlie Watts was indisposed or demurred. His close relationship with the Stones collapsed only after he became addicted to the heroin that was then around in abundance, and he had to be dismissed.

Charlie Roberts, one of ‘Fast’ Eddie’s closest friends and confidantes, and who was there from the beginning of Motörhead, remembers the band’s gig at High Wycombe Town Hall where Miller was checking out the band he was about to work with.

“That was when Eddie introduced me to Jimmy Miller, who was going to be producing their next record. Eddie said [hushed whisper]: ‘This is Jimmy Miller, man.’ And he then goes into his resumé, as if you didn’t know it, about the Rolling Stones, Traffic, et cetera, very much the Big Man.”

Bronze had their own studio where the label’s roster could record. Built in 1974, Roundhouse studio, next to the former engine shed-turned-North London venue that Motörhead had played so many times, boasted London’s first purpose-built 24-track desk.

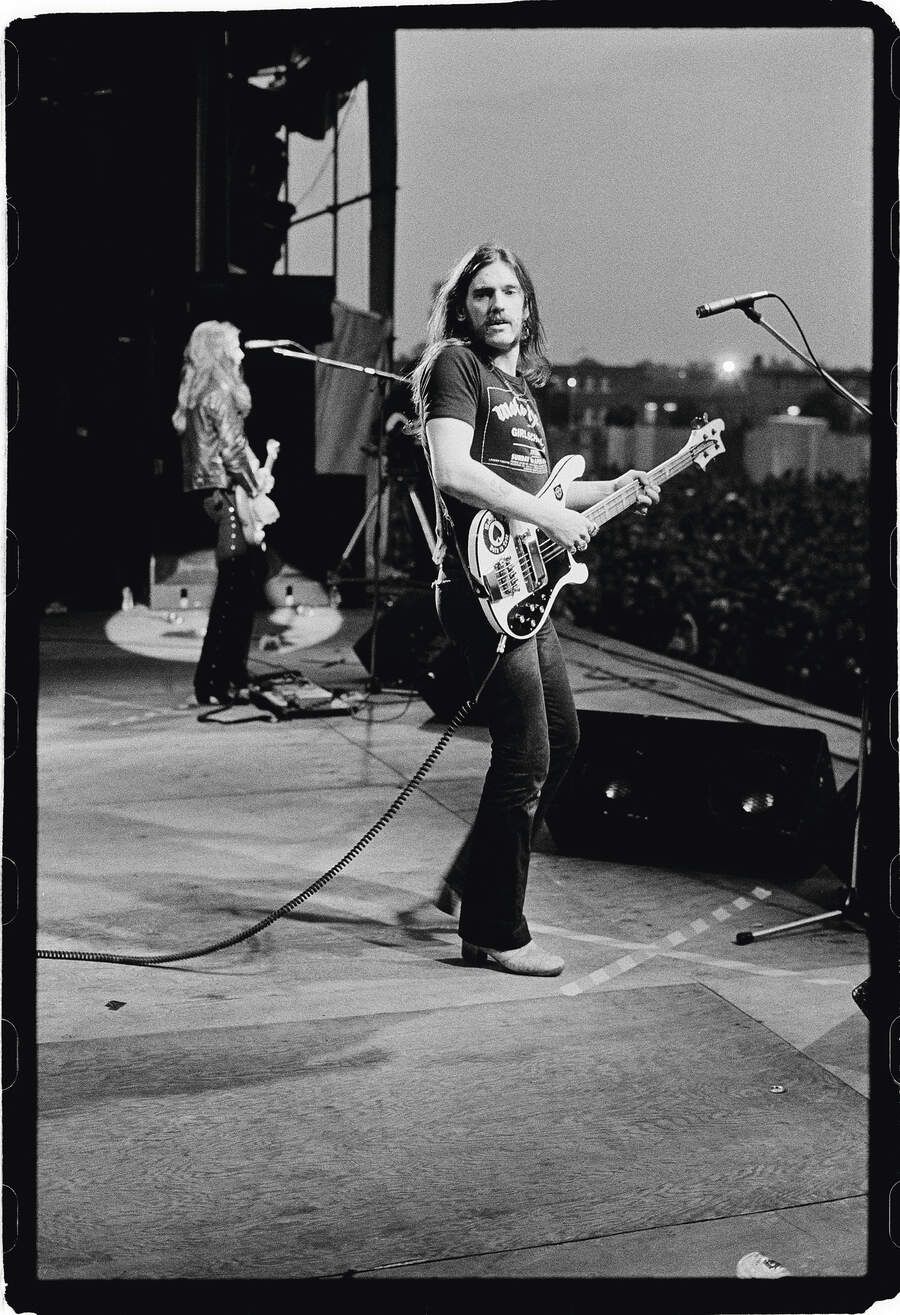

“We only had a fortnight to record,” Lemmy recalled in his memoir. “Considering our chequered recording history, however, it was a world of time for us. And besides, being quick in the studio has always been natural. The whole experience was pure joy.”

It was part of rock’n’roll folklore how Jimmy Miller had fallen foul of the popular 70s pastime known as trying to keep up with Keith Richards and found himself with the hefty heroin habit that curtailed his relationship with the Stones. That could have been a cause for concern considering Lemmy’s fierce anti-smack stance, but in his memoir he acknowledges that Miller was “messed up on smack for a long time, and he cleaned up for the first record and did really, really good”.

Trevor Hallesy, who was an engineer on Overkill, agreed. “On Overkill, Jimmy was there most of the time,” he said. “He was very good at getting a good vibe in the studio, getting a good take out of a band, actually making them all comfortable. He was a lovely guy and was a good psychologist with the band. I don’t remember him losing his temper, ever, in all the time I worked with him. He was good at keeping the status quo, that was one of his fortes. He was also very musical and a player himself.”

Miller intuitively plugged into Motörhead’s white-line-fever essence and gave the songs worked up previously huge, hairy studio bollocks. As Lemmy told Melody Maker: “His enthusiasm knocked us out. He got us to do arrangements and put in the finer parts. We already had the material, but he gave us a discipline. This album’s also a lot more diverse. For us, it’s sophisticated, and we’ve started to write our own material rather than relying on other people’s. Doing the album has given us an identity and a sense of direction.”

Eddie observed that “Overkill was a constant struggle to clean up so you could hear what was going on”.

The band worked fast, to the level of three songs being written in one night and recorded the next, including Lemmy’s favourite, Capricorn. “Eddie’s solo for that one, I recall, happened while he was tuning up,” recalled Lemmy. “The tape was running while he was fooling around with his guitar, and Jimmy added some echo. When Eddie finished tuning, he came in and said: ‘I’ll do it now.’ Jimmy told him: ‘Oh, we got it.’ That saved us some money!”

Describing the album’s recording in his book Lemmy & Motörhead In The Studio, Jake Brown gets an unusually detailed account from Trevor Hallesy, who recalls tracking Motörhead live to cope with the ferocity of their stage onslaught. Hallesy starts by making the point that “Motörhead was very professional; they’d been through it before and knew what was required. The band was well-rehearsed and had been playing these songs for ages, so when they came in the studio it was pretty straightforward, to be honest… quick and simple, they all knew what parts they had to play.

“Jimmy Miller might have suggested a few overdubs here and there, but they generally got it sorted out between themselves, what they wanted, before we got started tracking.”

Speaking in the ‘Melody Breaker!’ magazine included with 2019’s 40th-anniversary reissues of Overkill and Bomber, fellow engineer Ashley Howe described Motörhead as “a very interesting combination of musicians that had formed a perfect outlet to express their somewhat violent approach to music and to create a genre and style that no other band possessed.

“Motörhead were a raw band that didn’t need production other than to capture the essence of what they were and what they created. It was an interesting part of my recording career, so diverse from what I had recorded before, or ever again for that matter, but something I am proud to have been part of.”

Howe remembered Eddie as “a great guitarist but he had a tendency to get bored during the process of recording, and fall asleep on the couch in the hallway outside the control room. How, I don’t know, because it was never quiet, even through a sound-proofed control room. So when it came time to need him for overdubs, I would have the task of waking him up – not something you wanted. When you woke him, he would sit bolt upright swinging punches! So I quickly learned that a broom was the way to do it, and after several thrusts to his chest, he would take a few moments to realise it was me, and then calm down, and then get up.”

Hallesy remembers Eddie as the most sensitive band member at the recording sessions: “If there were any problems it was normally with him, and I don’t know if he was being a bit of a perfectionist. Eddie was a little temperamental during overdubbing. It wasn’t his fault, really… By that point in the recording of the album, there’s the rest of the band and the road crew and girlfriends and various things in the control room, and somebody’s concentrating on trying to do a guitar solo.

“You push the talkback button to speak to them and suddenly all they hear is a party going on where you are. I remember he did really lose it one time and stormed out in a huff because somebody had said something about his guitar playing and, unfortunately, the talkback button was pressed down at the time. He lost his cool, shall we say.”

Speculating on Eddie as a perfectionist, Hallesy is closer to pinpointing the guitarist’s meticulous recording ethos than even he seems able to appreciate after weeks of working with him. Overkill was Eddie’s first starting-from-scratch Motörhead album, a chance to exercise all the recording experience he’d picked up over the years.

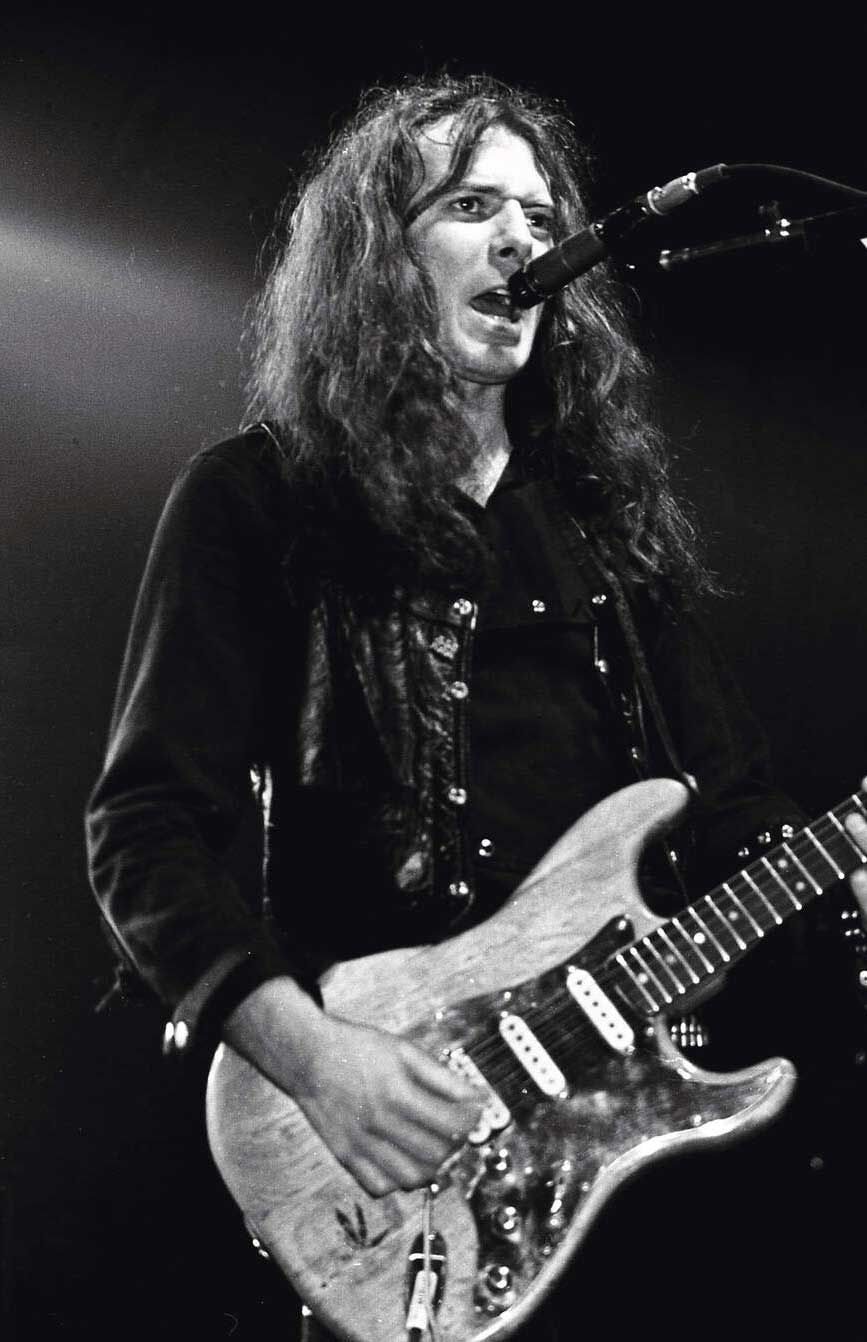

As those earlier recordings attest, his lyrical, blues-driven style was fully formed. If he had been content to whack out something quickly and join the studio party consuming wicked white powder and hard liquor, then Motörhead’s landmark albums certainly would have lacked the extra resonance of Eddie’s riffs, solos and walls of overdubbed raging guitar action. Even if Overkill suffered at the mastering stage, the work put in by Eddie still shone through.

Hallesy also recalls putting stereo delays on Eddie’s guitars, utilising the reverb chamber constructed in the catacombs linking Roundhouse with the old engine shed next door. “The studio had an area downstairs, which we completely tiled and put some speakers in and some microphones, and then we could send to it from the mixing console and use that room as a natural-sounding live room. During the mixing of that album, we also added synthetic reverb and delays to give it a bit of space afterwards.”

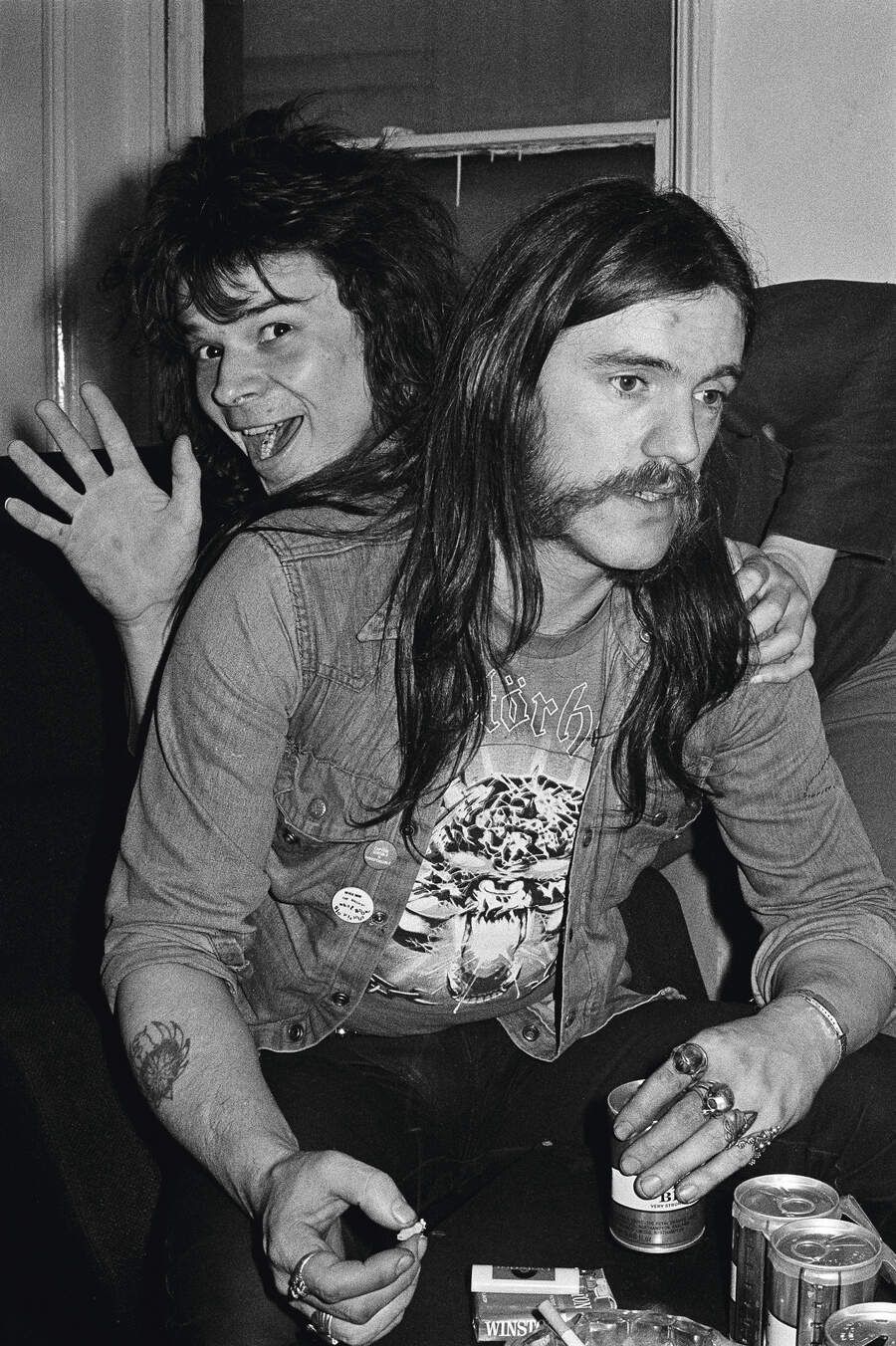

Just before Christmas 1978, I’d ended up in Dingwalls after a hard day’s pillaging record company parties. Leaning against the bar, my seasonal antics were suddenly interrupted by a visibly excited Lemmy insisting I come and have a blast of the album taking shape at Roundhouse studios nearby. I’d rarely heard Lem so enthusiastic about anything, and he raved in particular at Miller’s production and Eddie and Phil playing out of their skins.

The first track I heard was Overkill, sounding nothing less than devastating on the huge studio speakers. It was instantly obvious that Motörhead had cracked it as Phil invented thrash metal with that piledriving, double bass drum speed-tattoo recalling a pattern used by Cream’s Ginger Baker in his maniacal drum solos 10 years earlier, joined by Lemmy on turbo-cranked bass overdrive.

Manifesting like a mushroom cloud in reverse, Eddie’s cascading guitar entry acted like a blazing fanfare for Lem’s immortal opening shot: ‘The only way to feel the noise is when it’s good and loud’, to paving the way for the defiant title shout. And there were three endings! After it was over and the dust had settled, I must’ve resembled the coyote in Roadrunner cartoons, charred and spinning after being hit by an avalanche.

Charlie Roberts was another visitor smitten in similar fashion by the album’s monstrous title track: “I remember listening to the cut after they had finished Overkill, and when it finished there was absolute silence. I mean, you couldn’t say anything, it was the most incredible thing you ever heard. Really, there’d been nothing like it. There was just that minute of stunned silence, of ‘Wow!’”

Eddie said he hadn’t really anticipated Overkill being such a gamechanger for heavy rock, but willingly joined those enthusing over the track, later saying the false endings were simply celebrating both Motörhead’s sense of mischief and a certain invincibility they had gained from coming out triumphant from years of being up against everyone from the music biz to the rock press.

Due to occasionally muddy sound from mastering foibles of the time, Overkill wouldn’t sound as devastatingly powerful as it had erupting out of the studio speakers that night until it was remastered with half-speed technology for its 40th-anniversary box set.

This was the moment Motörhead’s inimitable sound reared like an earth-scorching Godzilla that instantly rendered conservative rock as redundant, lumpen and clichéd, pretty much finishing the job punk started with the gloriously no-holds-barred title track and gloriously robust bombardment that follows on side one: Lemmy’s anti-smack warning Stay Clean (complete with judderingly melodic bass solo), the jaunty (I Won’t) Pay Your Price, the demonic grind of I’ll Be Your Sister, and Capricorn, the album’s ‘ballad’.

If anything, side two raises the bar, now standing as one of the finest sides in Motörhead’s catalogue, starting with No Class’ hot-wiring the riff from ZZ Top’s Tush using Eddie’s favourite staccato power-chord punctuation, bolstered by Phil to emphasise its dirty, slavering onslaught.

It’s followed by the savagely elastic Mick Farren co-write Damage Case, the hell-for-leather Tear Ya Down and the slow-burning Metropolis – “We were a track short for the album and I’d watched the film the night before,” illuminated Lemmy. “We wrote that one in about ten minutes.”

Overkill then comes to a senses-demolishing finish with the magnificently brutal Limb From Limb, erupting from snarling, clarion-riff malevolence into a towering realisation of Motörhead’s roaring power at full pelt, capable of going off like a runaway train at the slightest provocation. A personal fave, I always felt it was dropped from the live set too early, and remains somewhat overlooked.

Bashing out a stop-press review for the September ’79 Zigzag, I frothed: “It is a mighty album, one of the densest, most overloaded noise assaults ever, ’specially the title track, which just don’t stop! (Philthy must have had his legs bionicised, welded to his drum-kit and turned on terminal overdrive!) Lemmy’s voice has lost a few more bricks since the last album (yes, this one is better) and his bass playing is more maniacal than ever. Fast Eddie tortures his guitar everywhere but won’t shy away from launching a supercharged wall of rhythm-power (try Limb From Limb). There is no other band operating anywhere near Motörhead’s enclosure.”

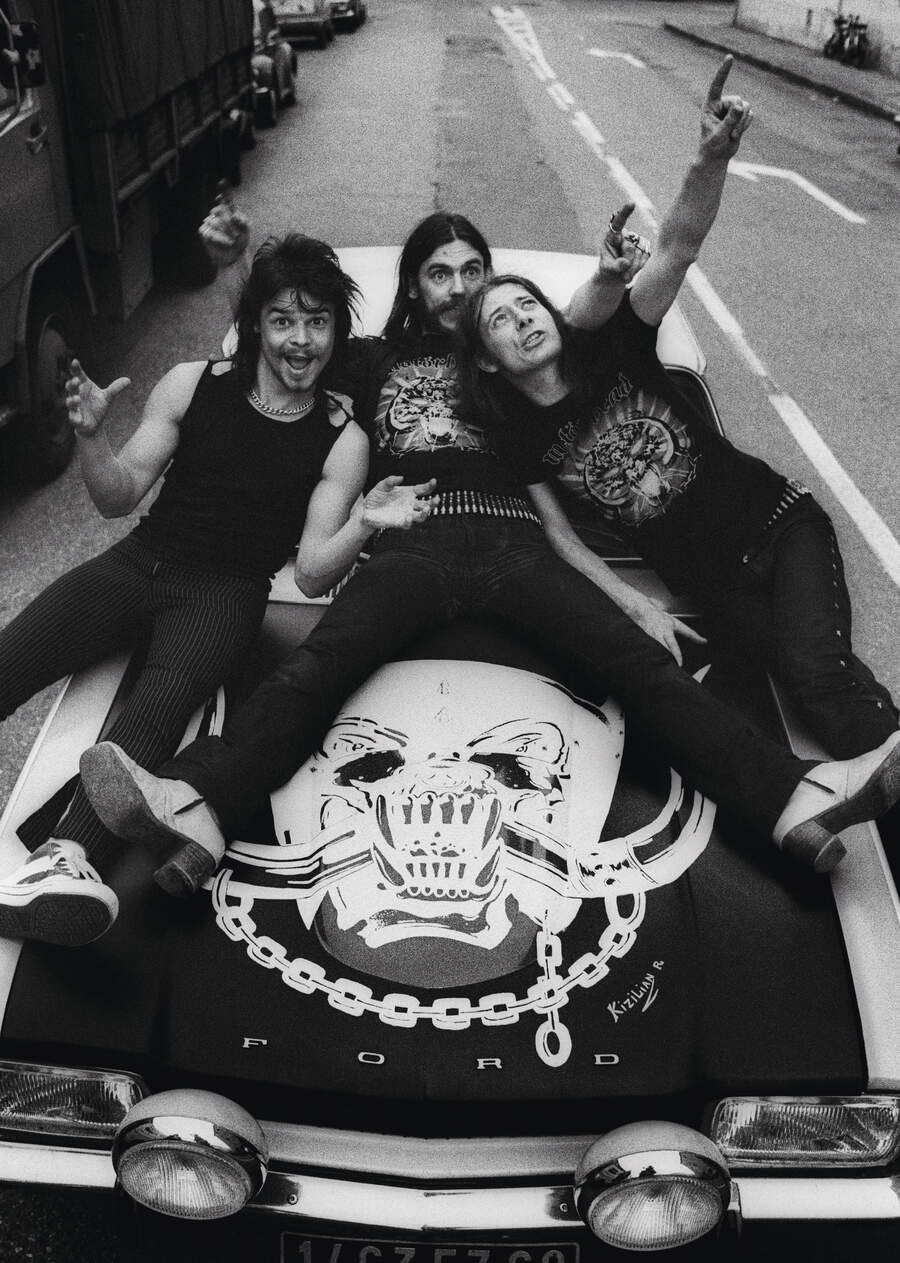

Trouncing predictable art-squeaking from music-press softies, Overkill sold 60,000 copies and reached No.24 in the UK when released in March. The title track single, with Too Late Too Late on the flip, became their first Top 40 hit, making No.39. “All of a sudden, things went mad,” said Eddie. “It was the record that really changed everything.”

Speaking to Joel McIver much later, he elaborated: “We had so many false starts and disappointments by the time Overkill came around in 1978, we had stored up a lot of energy and ideas – and we were just waiting for the opportunity to show what we could do. Also, we had a great following, and we always felt we owed the fans who had been with us from the beginning.”

Motörhead got to mime to Overkill on Top Of The Pops, and recorded seven of the album’s new songs for Radio 1’s In Concert at London’s Paris Theatre that went out on May 26. By that time the trio were on the road again for what would be their most successful tour yet.

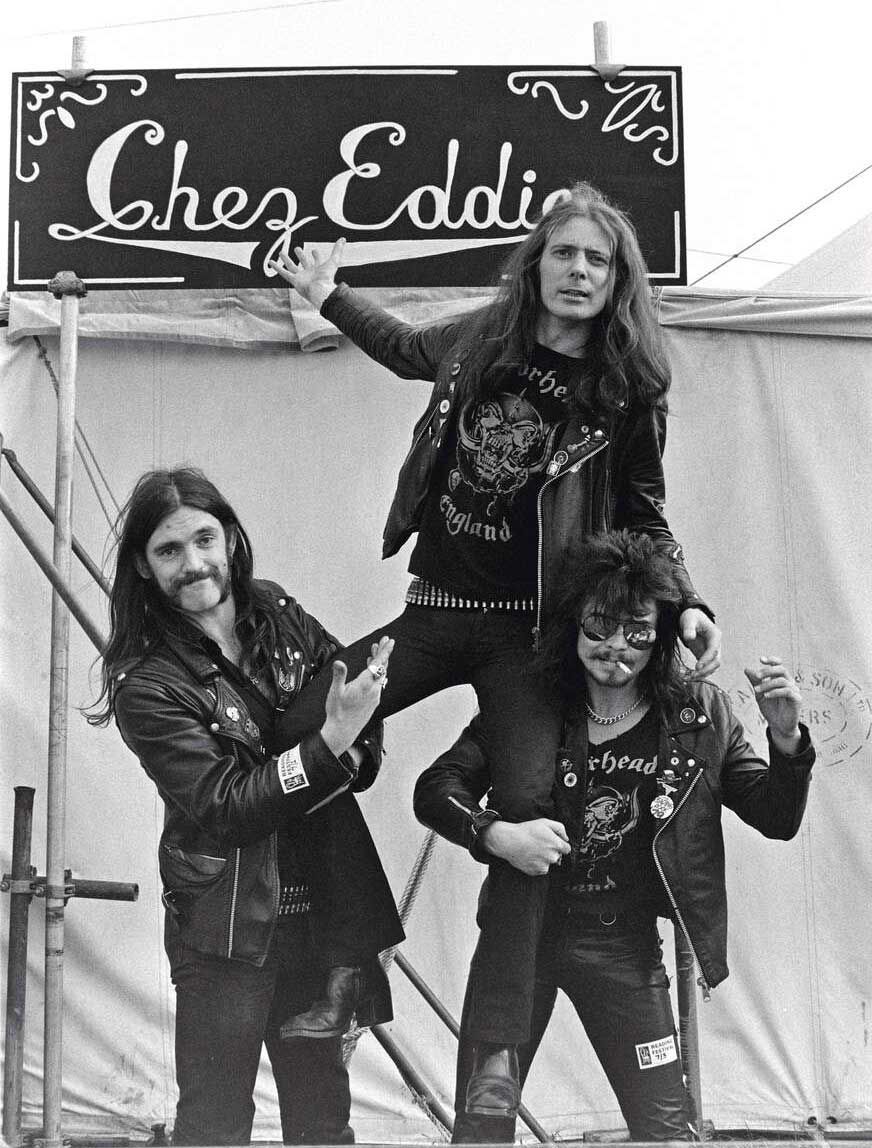

The Overkill tour would boast the second Motörhead gig programme designed by Steve ‘Krusher’ Joule, who had unwittingly come into the band’s orbit the previous year after designing Blondie’s Parallel Lines tour programme for Doug Smith’s Greybray Management’s merchandise arm.

“I didn’t actually work in the office, I would just go in with the roughs,” recalls Krusher. “When I went in to pick up my cheque, Doug wanted to see me in the office below. He said: ‘We’ve also got Motörhead on our books. They’ve got a tour coming up and we’d like you to design the programme.’ I always refer to it as the All About Being Loud tour. They gave me several pictures of Lemmy, basically all the same with just the words ‘All About Being Loud’. That was pages two and three. I went away and did it and never realised it was for the Overkill tour. That’s the first Motörhead thing I did.

“I used to sit in reception waiting to be called up to Doug’s office, and Motorcycle Irene would be on the desk. A few times I was there I noticed a brown paper bag on the desk. The doorbell would ring and this motorcycle courier would come in, with a helmet on. No words were said, he would just pick up the brown paper bag and walk out. After I’d seen this guy two or three times I asked: ‘Irene, what’s in the bag?’ ‘Oh, it’s for fucking Lemmy. A bottle of Jack Daniel’s, a gram of speed and some cash to play the fruit machines. It mostly goes out once a day.’

“Motörhead scared the shit out of me then. They hung out with Hells Angels, and Eddie got fucking hard as nails with all the skull rings and everything. Him and Philthy turned out to be fucking sweethearts, but Eddie was very serious. Don’t get me wrong, you could have a laugh with him, but he was a lot more fucking serious than those two. Phil wouldn’t be afraid to throw a punch, but it was Eddie who gave people a fucking battering, I heard.”

The Overkill UK tour kicked off on March 23 at West Runton Pavilion before traversing 18 of the biggest halls Motörhead had played yet, ending at London’s Lyceum Ballroom. Before every show, kids would be rubbing their eyes in disbelief as their three heroes hung out in the bar or strode around the audience checking out support act Girlschool. Obviously this couldn’t last long, but it helped lay the foundations for the colossal following to come. As I wrote more than 40 years ago, Motörhead might have been from the wrong side of the track, but as far as these kids were concerned they were on the right side of the fence – their side.

They could also now afford more lights, amps, speakers and smoke machines. The buzz of the breakthrough was also reflected in the band’s performances – confident, good-humoured and tight as a rhino’s truss. The set now went: Overkill, Stay Clean, Keep Us On The Road, No Class, Leaving Here, Iron Horse/Born to Lose, Metropolis, The Watcher, Damage Case, (I Won’t) Pay Your Price, Capricorn, Too Late, Too Late, I’ll Be Your Sister, ‘Train Kept A Rollin’, Limb From Limb and White Line Fever and Motörhead as encores.

Motörhead also returned to their early Friars Aylesbury stronghold on March 31; still the same bunch of down-to-earth nutters, with Lemmy spotted before the show playing the fruit machine in the Green Man punk pub next door. But the sense of struggle had been replaced by the confident air of a band on the rise. Thankfully, the tapes were rolling that roof-threatening night that went down as the loudest set ever experienced at the club in its then-10-year existence, their set providing a bonus CD or two extra LPs on 2019’s 1979 box set (which means I can hear exactly what was pinning me to the wall that night).

After steaming in with the double-header of Overkill and Stay Clean, Lemmy displays top Les Dawson form on his announcements, introducing Leaving Here as their first ever single “on Limp Records”, The Watcher as “psychedelic oldie time”, the new Capricorn as “a nice slow love song”, and Metropolis as “our Pink Floyd imitation number… it’s better than the Pink Floyd are these days”.

Lemmy dedicates Iron Horse/Born To Lose to the bikers, and banters with the warm audience on a hearty call-and-response interlude of “Bollocks!” before the set climaxes with Train Kept A’ Rollin’ and a blistering Limb From Limb, encoring with White Line Fever and, “just in case you’ve forgotten what we’re called…” the self-titled romp that saved Motörhead’s bacon in 1977.

Charlie Roberts came along that night, remembering: “Eddie didn’t like going home when he was on tour. We were in London for a day, so we booked into the Portobello Hotel – just basically to drink, because this was the 70s, when places closed early. We wanted to play poker dice. When Eddie and I played poker dice it was like: ‘How much have you got?’ ‘I’ve got 40 quid.’ ‘Okay, I’ve got 40 quid’. So when we finished playing, we would make sure we got the same money back, as we wouldn’t take money off each other.

Eddie and I were down in the bar and, sitting over on the next table, minus Wilko, were Dr Feelgood. Eddie and I were with the poker dice, and even though we’re not playing for keeps it’s intense. The Feelgoods were watching with interest, and asked: ‘Can we join in?’ There was four of them, so we did that. By the time Eddie and I had finished we’d paid each other what we owed and were still in pocket. That was the lovely thing about London back then. We’d be bumping into people all the time. We’d come from Aylesbury, and the Feelgoods from playing somewhere in London.”

Charlie has another story that gives an insight into Eddie at the time, while also showing the violently tribal nature of the era taking place after the official opening gig at St Albans Civic Hall on March 24: “You know how Eddie and Phil used to have an occasional fistfight, but Lemmy always backed off? Sometimes I feel that a lot of the problems caused within that sphere were caused by drink and chemicals. There was also a lack of understanding of Eddie. With Eddie, not everything he said was how you needed to interpret it. Sometimes he was giving you a polite message, like: ‘Well alright, but I ain’t fucking comfortable.’

“They’d done the gig at the Civic Hall. There was me, Eddie, Lemmy and a couple of girls who had a car parked out front and were going to drive us back to London. The girls are in the car, and I get about halfway across to them with Lemmy and Eddie when we start getting pelted with stones by a group of youths. Lemmy is like a fucking greyhound, heading for the car. Eddie? No, he’s going to fight the c**ts – and there’s quite a few of them.

“They were probably skinheads, and we were guys with long hair. The road crew had left so there was just the two of us, as obviously Lemmy was out of the equation. I had to grab hold of Eddie and physically pull him towards the car. We got in, and just as we’re going off, a stone hits the back window and breaks it. That’s how close we were to a huge fight, with no crew. We’d left the safety of the hall, but Eddie still wants to go back and fight.

“So Lemmy’s sitting in the front, this girl’s driving and there’s three of us in the back. Lemmy decides: ‘I want a fag now’, so he lights up and opens the fucking window! We didn’t have any back window, so we’re getting sucked through the back of the vehicle as it bombs along! Anyway, we made it back to London, all was okay.”

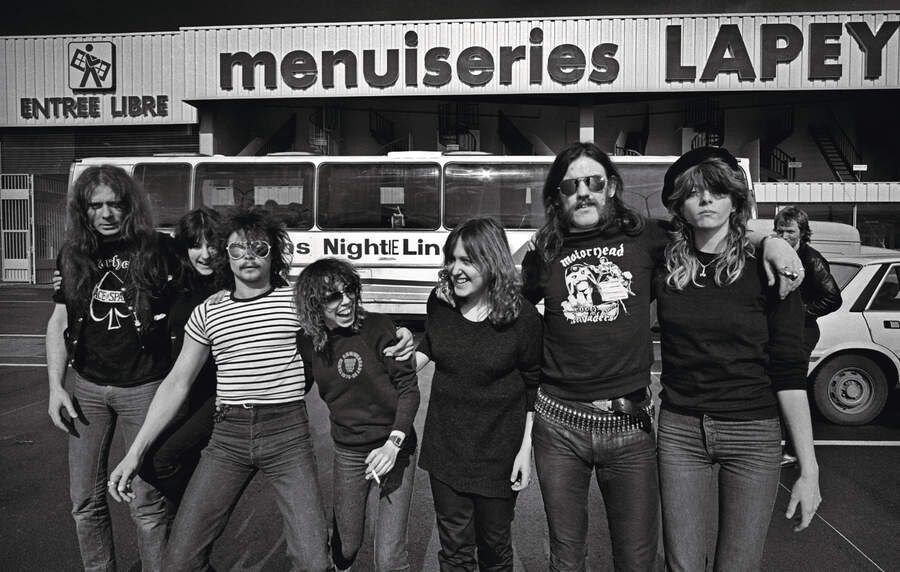

Supporting on the tour were South London hellraisers Girlschool, soon to be inextricably linked with Motörhead for years to come. After childhood friends singer-guitarist Kim McAuliffe and bassist Enid Williams formed Painted Lady in early ’77, they became Girlschool with the arrival of guitarist Kelly Johnson and drummer Denise Dufort the following year. Playing the gig circuit could see them slogging around France and Germany, or supporting Sham 69, or homeboys the UK Subs in London. Then an old friend, Phil Scott, who’d started the City Records label (who released the UK Subs’ C.I.D.) asked Girlschool if they’d be interested in putting out a single.

Released in January ’79, Take It All Away suffered when City Records went down, but did reach Doug Smith, then looking for a support band for Motörhead’s spring UK tour. The band had seen the single as a demo on wax, so their plan had worked when they signed with Smith and landed the tour spot. It proved a marriage made in heaven as both bands clicked in an explosion of leather and force-10 hard rock’n’roll.

Both bands shared the same wariness of being lumped in with heavy metal; Lemmy famously said Motörhead’s music was rock’n’roll, and Eddie having reached into his coming of age with the blues through The Yardbirds. Speaking to Zigzag, Kim stressed: “I hope we’re not a typical heavy metal band. We like the power of heavy music, but we don’t want to regurgitate the same old riffs again and again like a lot of new bands are doing. We’d like to do something a bit better.”

“The tour was crazy, it really was,” she laughed. “A mad three weeks. Everyone said we looked so ill after, sort of wasted.” Asked about the headliners’ fearsome image by Sounds’ Phil Sutcliffe, Kim said: “They turned out to be the nicest guys you could meet. They’re just a bunch of twits. I like them because they’re not putting on any sort of false image.”

Speaking to Kim 43 years later, she’s she’s now living in the Essex countryside raising rescue rabbits when not touring with the latest Girlschool lineups, now minus Williams and, sadly, Kelly Johnson who succumbed to cancer in 2007.

“The way we met [Motörhead], we’d just released the first single, Take It All Away, and it just happened to coincide with the fact that they were looking for a support band for their first major British tour, the Overkill tour. We’d been knocking about for a couple of years on the circuit, playing punk clubs where the audience thought we were heavy metal and heavy metal clubs that thought we were punk, so we didn’t really fit in anywhere, but we kept on regardless.

“Then we met Lemmy. He came down to rehearsal and agreed, with the others, to invite us on to the tour. Talk about being thrown in the deep end, because we all shared a coach together, a minibus. From day one it was just mayhem, as you know from being on the road with them. Of course, we formed strong friendships with ’em, to say the least!”

In Kim’s case this meant getting together with Eddie on the tour, followed by Philthy later. Enid Williams has less than fond memories on a personal level after feeling the full force of Eddie’s booze-fuelled temper.

“When we went on the Overkill tour, I always went to bed quite early, cos they’d stay up partying every night and I didn’t drink very much,” she recalls. “This was the first time we had this sort of situation, really. Motörhead weren’t that big then, it was small theatres on the circuit, a respectable crowd but not packed out. We were getting paid peanuts and six of us shared a bedroom – four of us sharing a bed together and the two guys slept on the floor. We really were slumming it. It was horrendous conditions.”

Throughout those whole five years I spent in Motörhead’s close orbit, Carlsberg Special Brew was the beer of choice, being a cheap, super-strong way to get pissed quick. Before Tennent’s Super lager appeared as its nearest rival, Special Brew was the alcoholic derelict’s favoured beverage that also provided an essential function for Girlschool’s keen party animals.

“There was a load of partying going on and in those days it was all around Special Brew,” affirms Enid. “Kim had been going out with our roadie/tour manager/driver/ everything, also called Kim, for a couple of years. He’d been there since the beginning and was amazing. Kelly encouraged her to go crazy and they were drinking like fish. And then Kim went off with Eddie. It was a bit shit, really, because the other guy’s there every day right next to us. Talk about uncomfortable.

“One night I remember Kim and Eddie were in this hotel room, a cheap bed-and-breakfast thing. They were having a row. I’m trying to sleep in my little bed in this very small single room. I shouted through the wall:‘Could you keep it down, please?’ Next thing I knew, Eddie’s smashing on the door. I was surprised and genuinely frightened.

“I don’t know how long Eddie and Kim lasted, but a while after they split up she was with Philthy and they used to get very drunk and fight. Then Eddie had a French girlfriend and I think they threw bottles of vodka at each other’s heads. It got quite nasty. I didn’t really know Eddie at all at that point – and I stayed away from him.”

As I later found out myself, such relentless dousing in high-strength alcohol – and there was also a lot of vodka and Jack Daniel’s bourbon around – could easily lead to various extreme forms of behaviour and, if continued, paved the way for full-blown alcoholism and all that comes with it if not kept in check (unless you were Lemmy). Eddie became a classic example by the following decade, but, even in 1979, as Enid found out, the mix of strong booze and his volatile temper could be a scary one.

With Girlschool still acquitting themselves well and gaining many lifelong fans on the tour, a deal with Bronze Records soon became such a possibility that the label asked for demos, which Eddie offered to produce.

Kim recalls: “Bronze wanted a demo, so Eddie produced three songs. I still remember he used to drive us to and from the studio. One night he was driving me back home and it was thick fog, so this shows you how long ago it was in London, when we used to have all the big fogs. It was probably about midnight or something. Eddie had this lovely old Rover, and we’re driving along, and he couldn’t see a bloody thing. ‘I feel like fucking Captain Kirk boldly going where no one’s gone before!’ he said.

“We were laughing our heads off cos he literally could not see a thing. We made it safely back, though, and that was one of the funny times we had. He had a real sense of humour, but even though he did seem quite laid back, at times he wasn’t. Famously, him and Philthy were always at it hammer and tongs.

“We toured with them many more times throughout the years,” Kim continues. “We were lucky enough to be on their first major British tour, and then we were actually on their last tour before Lemmy died, forty years later. So we did all that with them and loads in-between.”

Reminiscing in Melödy Breaker!, the 1979 box set magazine, Kim declares “I loved them! In fact I saw a lot more of Phil and Eddie than I did of Lemmy, especially when he went to America… I was always in touch with Eddie right ’til the end [2018]. All those songs were just amazing, and they sound brilliant today.”

Kim homed in on Eddie’s contribution to the classic line-up when we spoke: “I think he was a pretty underrated guitarist, but he was bloody brilliant. I mean, some of those riffs he came out with, they’re just unforgettable, aren’t they?’ You just don’t get riffs like that these days. And he used to look so great on stage, of course. Eddie used to stand out, he looked fantastic.”

“The Overkill tour was the first really big theatre tour that Motörhead had done at that point,” recalls Enid Williams in the same magazine. “There’s a certain vibe when a band is just on the cusp of making it. I mean, we’d never done a big tour like that. And musically it was really memorable because their sound wasn’t like anything you’d heard before.

“Obviously Lemmy loved the stuff he’d grown up with and the very early rock’n’roll, and you can detect bits of Sex Pistols and stuff like that, but nobody had played drums like that before, and Eddie was just the perfect guitarist… I can remember standing on stage, watching them play Overkill and the walls were shaking, and it was like nothing else you’d ever heard before.”

It wouldn’t end there, as Motörhead maintained the momentum of their upward trajectory by recording their second album in the space of a year and coming up with a stage show that was like nothing else ever seen before.

Make My Day: The Rock’N’Roll Story Of Fast Eddie Clarke – the 4CD set and official biography by Kris Needs and Mariko Fujiwara – is out now via BMG. Extract printed with kind permission.

SUBSCRIBE TONIGHT prime video

Source link